Along the Surface

Volume 2, Essay 2. An Unwelcome Element of Lived Human Experience.

Introduction

To be human is to have the ability to perceive pain. The lived experience of being human is to feel pain of varying intensities, even in the absence of a noxious stimulus. Pain has something, and in extreme cases everything, to do with being and existence. As a term, pain itself needs clarification. Pain in Dubin and Patapoutian (2010) “has been defined as a ‘complex constellation of unpleasant sensory, emotional and cognitive experiences provoked by real or perceived tissue damage and manifested by certain autonomic, psychological, and behavioral reactions’” (p.3760).

The topic at hand is severe pain. A pain so intense that it sears, tears, gnaws, burns, causes misery, suffering, agony, and despair. Severe pain changes posture, facial expressions, and breathing, and pain can become part of identity, grow, and modify who we are. When “pain” is written here, it indicates severe pain, unless context suggests otherwise. Sensations of severe pain, particularly severe pain, can be produced internally, given, and received, caused by exogenous sources, or by the suggestion of them (Maturana, 1983). Severe pain is an interesting area of study, as it anecdotally appears that the majority of the population has experienced or is living with severe pain and can articulate the lived experience of it. Following the study of pain and being, this essay explores how music and art can connect with, make explicit, and even amplify severe pain already within being, before exploring distinguishing pain, and pain and identity.

A further step is taken with the work of Maturana through distinguishing pain that was in the process of occurring but was not recognized and lived until it was distinguished. The understanding is that if pain is not distinguished, there is no pain. Maturana’s use of distinction is initially extreme; a hardline approach taken to distinctions where nothing exists until it is distinguished (Maturana, 1992; Maturana & Poerkson, 2011). This position can be softened if the direction is followed that pain preceded the distinction, but was not noticed until either it was distinguished, or it was distinguished as the pain became overwhelming. This is a forced distinction that is an adaptation of Maturana’s earlier writings.

Pain can be severe, enduring, and worsening. It can cause disabilities, it can change the course and content of a human’s life, and it can persist with no solution. Severe pain can change a person’s identity, and it can change their facial expressions and how they breathe, act, think, and move. The human who existed pre-injury and severe, lasting pain vanishes, and a new, different, pained human emerges. Its depth, richness, and harshness make pain an interesting and worthy topic for essay number two.

To aid the reader, it is recommended that essay number one be read first to gain an understanding of the setting this essay appears and, more importantly, the author’s use of the terms “existence” and “being”" “The Issue of Common Existence Occluding the Nature of Being.”

Dedicated to all who suffer.

Below is a biological account of pain. It is not graphic, but may evoke images and sensations.

Being and Pain

Pain not related to emotional pain in existence’s mind and self-conscious is found in being’s sensorimotor structure. Pain receptors perceive pain, or what are formally known as “nociceptor sensory neurons” (Pinho-Ribeiro, Verri & Chiu, 2016, n.p.), or simply “nociceptors.” These sensory neurons, which belong to the peripheral nervous system, “protect organisms from dangers by eliciting pain and driving avoidance. Pain also accompanies many types of inflammation and injury” ( Pinho-Ribeiro, Verri & Chiu, 2016, n.p.). Nociceptors have also been referred to as “cutaneous nerve fibers” that have sensory functions, “nerve fibers,” “cutaneous (meaning anything related to affecting the multiple layers of skin) sensory nerve fibers,” which are located in the soft organs, muscles, and joints and “bare nerve endings of primary sensory neurons innervating the skin, muscle, and viscera” (Norcliffe-Kaufmann & Gutierrez, 2014). Located along the surface of skin, joints, and organs, nociceptors are ubiquitous, as is the body’s capacity to perceive pain. The perception of pain initiates at the bare nerve endings, which are tendrils from the primary neuron. While they are bare at the nerve tip, Schwann cells surround the remainder of the nerve and create a myelin sheath and perform additional functions (Kendroud, Fitzgerald, Murray, & Hanna, 2022).

As sensory nerve fibers, nociceptors “respond to mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli” (McMahon & Snider, 1998, p.629). There are nociceptors for each stimulus and other specialized nociceptors, including mechanoreceptors, thermal receptors, polymodal receptors, and silent receptors (Kendroud, Fitzgerald, Murray, & Hanna, 2022). Silent receptors are unresponsive to the initial stimuli of heat or pressure; “they become responsive only after tissue damage causes the release of inflammatory molecules” (Kendroud, Fitzgerald, Murray, & Hanna, 2022, n.p.). In action, the authors explain that nociception is “the neural process of encoding and processing noxious stimuli” (Dubin & Patapoutian, 2010, p.3761). Alternatively,

Nociception provides a means of neural feedback that allows the central nervous system (CNS) to detect and avoid noxious and potentially damaging stimuli in both active and passive settings. The sensation of pain divides into four large types: acute pain, nociceptive pain, chronic pain, and neuropathic pain.

Nociceptive pain arises from tissues damaged by physical or chemical agents such as trauma, surgery, or chemical burns (Armstrong & Herr, 2023, n.p.).

When nociceptic neurons are stimulated, they send “high-threshold noxious stimuli to the central nervous system” (Armstrong & Herr, 2023, n.p.). The signal from the nociceptive neurons may either be routed immediately “in a spine reflex loop, producing a rapid and reflexive withdrawal, or transported to the areas of the brain responsible for integrating the information with higher-ordered sensations such as pain (Armstrong & Herr, 2023, n.p.). Said another way, “Activation of the nociceptor initiates the process by which pain is experienced, (e.g., we touch a hot stove or sustain a cut). These receptors relay information to the CNS about the intensity and location of the painful stimulus” (Dafny, 2020, n.p.).

There are two primary nerve fibers involved in nociception: A and C. While it is more complex than presented here, it is sufficient to understand A fibers as myelinated, which innervate hairy skin, and C fibers as unmyelinated, where the speed of transmission from the nociceptors depends on myelination and the diameter of the fiber sending impulses away from the nerve cell to other parts of the body (axon). Ringkamp and Meyer (2008) write that:

Unmyelinated C-fiber “nociceptors are responsible for the burning pain sensation from noxious heat stimuli and from prolonged mechanical stimuli. Myelinated A-fiber nociceptors are thought to be responsible for sharp, pricking pain associated with intense heat and sharp objects (n.p.).

Kendroud, Fitzgerald, Murray, and Hanna (2022) add additional layers of insight into fibers.

A-delta fibers are lightly myelinated and have small receptive fields, which allow them to alert the body to the presence of pain. Due to the higher degree of myelination compared to C-fibers, these fibers are responsible for the initial perception of pain. Conversely, C-fibers are unmyelinated and have large receptive fields, which allow them to relay pain intensity (n.p.).

Thresholds for nociceptors have been established. For example, “nociceptors respond to mechanical forces of only 10mN (millinewtons) or so, forces that, interestingly, are not generally rated as painful in humans” (Snider & McMahon, 1998, p.629). Dubin and Patapoutian (2010) explain that the threshold for heat pain perception is between 104°Farenhit to 113°Farenhit. The authors continue and explain, “The threshold for pain perception to cold is much less precise than that for heat, but is about 59° Fahrenheit” (Dubin & Patapoutian, 2010, p.3765). Returning to A fibers, Dubin and Patapoutian (2010) refer to a class of fibers known as A-HM Type 11, stimulating “hair skin responding to temperatures slightly cooler than the perceptual pain threshold for heat are proposed to mediate first pain in humans. These fibers rapidly activate, adapt during prolonged heat stimulation, fatigue between heat stimuli, and are sensitive to capsaicin” (p.3764). While only related to thresholds, the previous quote brings greater clarity to nociceptor nerve fibers ( Pinho-Ribeiro, Verri & Chiu, 2016).

On a daily basis, humans seek medical attention after injuries caused by mechanical force, exposure to noxious chemicals, high heat, extreme cold, or chemical stimuli. Armstrong and Herr (2023) explain that in the case of these injuries, humans are only aware of them due to the nociceptors distributed across their bodies. The authors continue, “Nociceptors transition acute pain into inflammatory pain when the duration of stimulus persists, and nociceptors release their pro-inflammatory markers, sensitizing local, responsive cells” (Armstrong & Herr, 2023, n.p.). This activity takes place along the surface.

The previous essay focused on the closure of the nervous system, indicating that stimuli do not determine what happens within the nervous system, but do not determine the response (Maturana, 1983). An important capacity of the closure of the nervous system is its ability to generate, through its internal dynamics, states of neuronal activity, including nociceptive pain. Anticipation may be possible if the states of nociceptor cells are generated interneally from activity at the eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and other sensory surfaces.

Pain is described as having different qualities and temporal features depending on the modality and locality of the stimulus, respectively: first pain is described as lancinating, stabbing, or pricking; second pain is more pervasive and includes burning, throbbing, cramping, and aching and recruits sustained affective components with descriptors such as “sickening”….As opposed to the relatively more objective nature of other senses, pain is highly individual and subjective and the translation of nociception into pain perception can be curtailed by stress or exacerbated by anticipation (Dubin & Patapoutian, 2010, p.3760).

The Art of Severe Pain

A certain feeling of recognition may be derived from the moment when an obscure, sorrowful artist’s self-proclaimed “dead music,” or the “worst music I could make,” discovers, evokes, connects with, and amplifies feelings of severe pain. The music begins suddenly. A tortured synthesizer plays foreboding, menacing, and whirring tones. A reverberating, repeating, twisting, and grating array of noises, similar to the descending of an airplane’s landing gear, adds complexity and further distress to the sounds. There are random samples from non-English speaking films distributed throughout, and constant meddling with effects and sounds. The top layer is constituted by the random, distorted, echoing, initially croaking, turned frustrated screaming voice of the artist exclaiming “no more!” and “you can’t escape from here!” The disturbed voice, embodying pain uncomfortably and obtrusively, penetrates the distressed barrage of random noise, yet not wholly without patterns. To most, it is a violent cacophony of painful sounds. For some, there is music in the pain, and pain brought forth through the music. There may be clarity in knowing the pain inside oneself, for this is how being and the mind, and self-consciousness of existence move through time. The music is composed in a manner in which the internal dynamics of the nervous system may trigger the sensation of nociceptor pain by changing states of sensory bare nerve endings to give the feeling of approaching or actual tissue damage or noxious cold without either being present (Maturana, 1983).

Such music lies beyond the margins of margins. The artistry above is part of a genre centered around death, dying, pain, and other extreme themes, popularized outside of the United States. Each cassette, vinyl, and CD produced by related artists serves as an instrument of introspection sharply thrust into the relational web that constitutes human life. This infiltration of conspicuous albums is composed to grate along inner and outer surfaces by exogenously introducing music intended to align with or evoke the severe physical pain only talked about in doctors’ offices, with family, or close friends. Having severe pain and even death projected onto and into the human deliberately through music beyond what film alone could ever hope to accomplish forces a reckoning with severe pain itself: torture, agony, despair, excruciation, and suffering.

The music is heard as real as it feels. It draws out of the abyssal depths and entangled complexity of being and into existence. A severe pain that dwells in being may not yet have been openly and inwardly given a name until its essence is heard in the music. It is pulled outward and given a clear presence in being, and starts to take up space.

Music can resonate with and even locate and bring forth severe pain, just as Käthe Kollwitz does with lithographs.

Here, Kollwitz expresses misery, agony, suffering, and endless excruciating pain. A person steers the individuals in front of the beam, who are hunched over due to the strain of dragging the moldboard, share, and colter through the dirt to till the field. The replacement of animals with humans (not without precedent) adds a thick layer of severe, inescapable pain to tilling the soil. Rows have already been plowed, yet an expanse remains beyond what Kollwitz made visible. If the pain the individuals experience increases, it will become unbearable. Every day life can imitate the plight of those pulling the plow through the dirt. The monotonous and relentlessness pain that often accompanies dragging the beam and its blades through tough rocky soil can be felt elsewhere, even if there is no real noxious stimuli. The emotions of pulling the plow align with the experience of having an everyday experience, whether in existence’s mind and self-conscious, in being, or both. In everyday life, the plow may feel as if it is never untethered from the one pulling it, and the grade never gets any flatter. Still, the pulling and plowing continue, and the nociceptors are steadily sending noxious stimuli to the brain as the ropes tear and gnaw at the tissues beneath. The silent nociceptors become activated once the inflammation begins. In some cases, being and existence both may feel like there is pain, even if there is no source of pain present.

Distinguishing the Pain(s)

An artist creating music about severe pain (likely in pain) may provide the right sounds for a human to distinguish pain in their being for the first time. According to Maturana (1992), if pain is distinguished, it exists; if it is not distinguished, it does not. Pain is distinguished, cleaved from its surroundings, and given a past that explains the origins of the now-recognized pain. In distinguishing sources of pain, existence’s understanding of being in pain is more complete. To engage in the hardship of distinguishing all of the pain in being is to add misery to a sense of the whole human. Pain before it is distinguished is present in being but covertly exists before it is acknowledged within it. Covert pain remains illegitimate as it has yet to be brought forth. Pre-distinction pain occurs, but it is not yet made legitimate and brought into humans’ awareness.

But at the same time we distinguish ourselves doing what we do. Listening, observing, in experience. And by speaking about experience I refer to that which we distinguish as happening to us. I'm listening or I'm bored, I'm interested, I'm tired, oh my back! All these are distinctions of what happens to us in that moment. If I don't distinguish that my back [aches] , my back doesn't [ache]. Aha, when I distinguish I may say “Oh, it has been [aching] all this afternoon.” And we know this. We have been doing things and suddenly we make a distinction that we extend to the past. But unless we make the distinction, nothing happens (Maturana, 1992, p.4).

Pain of any variety, whether it be emotional or physical, minor or severe, fills being with a complex essence. The kettle fills the mug, and often fills it over. Distinguished pain adds, while it can, to the lived experience of being human. Some levels of pain can be distinguished in a positive sense as motivation in athletics, or an avoidance pattern of behavior that reduces future encounters with sources of pain. Pain in the middle of the gradient may not be chronic and ebb and flow over time, but it makes the sufferer more appreciative of its absence. Severe pain adds agony, misery, and torment to the lived experience as long as it endures. Even severe, it still adds, before it has the potential to take away. There may be enlightenment through suffering. It is possible that there may be moments of clarity in severe pain, insight gained, and associations made that did not exist before the onset of severe pain. Understanding may be achieved, and an appreciation for life without pain. Even severe pain adds to the experience of being through activated nociceptors.

Part of living is to continue to distinguish sources of pain arising through language as they occur in being, and their place in the mind and self-consciousness belonging to existence. The pain is either exacerbated or dulled by the behaviors of existence. Bringing pain, more pain, into existence is the only potential way to make it less than. As noted before, pain is constitutive of humans. However, this is not to make pain supreme, but instead an important element distinguished by existence in the mind, self-consciousness, and being.

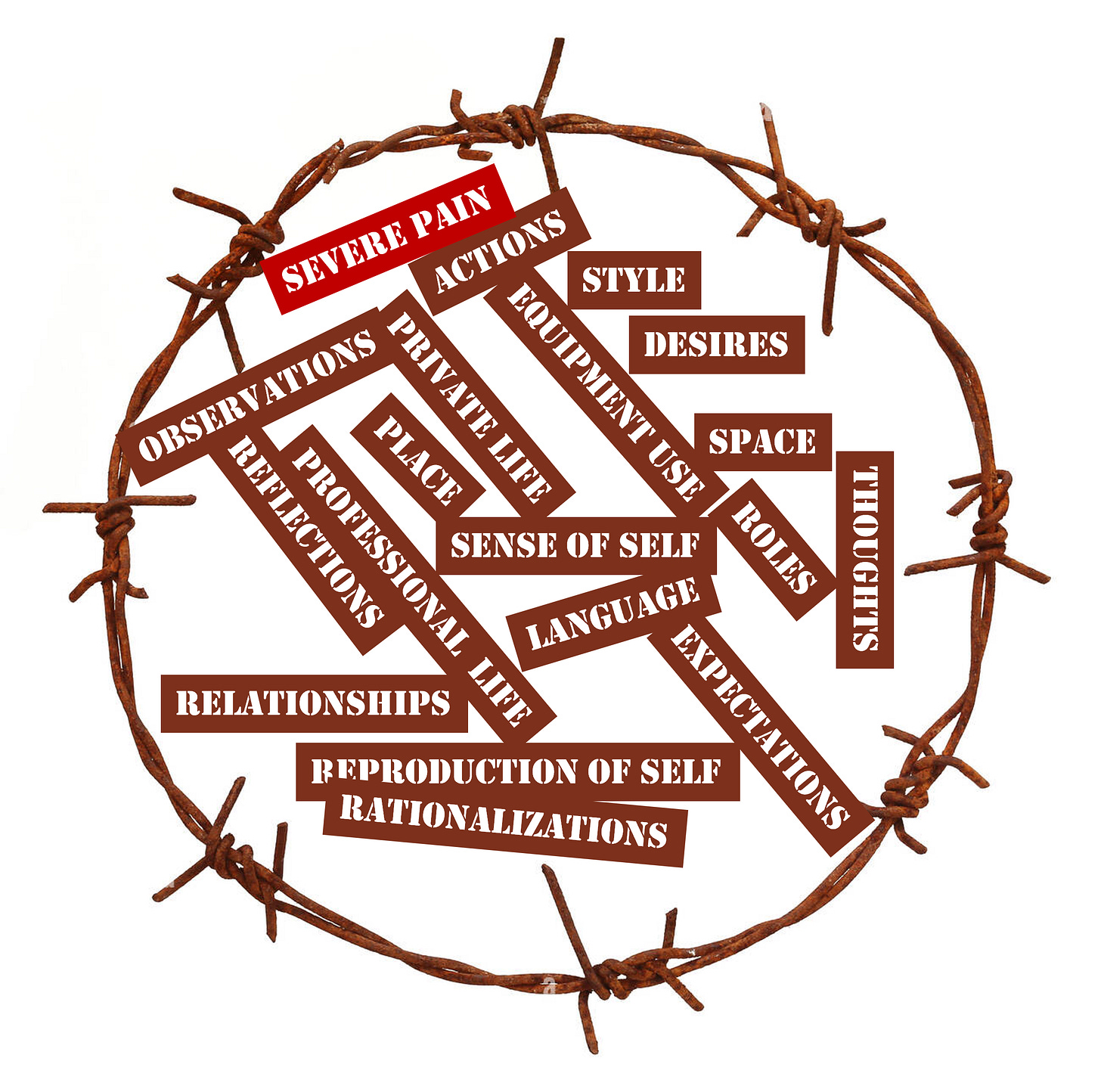

Pain and Identity

The human form is arranged in such a way that pain is inevitable. Its external surfaces and some of its internals await stimuli that will be perceived as pain. How being can be in nociceptor pain has been studied. Focus now shifts to how humans can become pain through integrating it into their identity. Identity, as pictured below, is a bounded entity with impermeable areas, the rusted barbs on the rusty wire, and permeable areas in between the barbs where consciously or unconsciously elements, namely severe pain, are allowed to enter and become part of identity.

A severe pain, such a tissue damage, burns, or the long-term deleterious effects of the inhalation of noxious chemicals, can linger long after the initial stimulus is gone, even for the rest of one’s life. The earlier solution to pain was not to distinguish it, but this was described as illegitimate. Instead, pain must be distinguished by drawing a boundary around it, and bringing it forward into our awareness endowed with properties and a context granting it significance, meaning, history, and a future (Maturana & Poerkson, 2011; Mingers 1995). This process, Maturana (1992) describes as requisite for anything to exist. When confronted with pain so overwhelming, it forces the afflicted to distinguish it while it is endured. The distinction is not optional, though it still does occur. From the distinction that adds the temporal elements of past and future and injury and healing, as well as significance, properties, and context, there is another boundary with properties unique to each human called identity. Transitioning from pain that is recognized and lived experientially, to identifying with pain and making it part of who one is at the level of their existence, pain becomes part of who they are, their identity. Pain cannot always be distinguished and set aside. In some cases, gradually or all at once, pain can be so severe that it barges across the semipermeable boundary of identity and unconsciously becomes a dominant component of identity. Severe pain’s integration into identity will alter how the other components of identity are perceived, weighed, relate to one another, and hang together. Pain may clear away that which was once important, turn negative what was once positive, and change the way the constitutive elements dynamically interact to product the emergent property of “identity” that is created through the interaction of components and not their aggregation. Recruiting being and existence, a prominent shift will occur in mood or emotion (moods are sustained longer than emotions), which is far from inconsequential. As pain becomes identity, it is probable that it will create a shift toward negative emotions that embody a human’s pain, including fear, anxiety, aggression, grief, and helplessness. As mood and emotions shift, the human changes.

In a way, a change of emotion or mood is a change of brain and body. Through different emotions, human and non-human animals become different beings, beings that see differently, hear differently, move and act differently. In particular, we human beings become different rational beings, and we think, reason, and reflect differently as our emotions change. We move in the drift of our living following a path guided by our emotions (Maturana & Verden-Zöller, 2008, p.38).

As mood or emotion shifts to represent perceived severe pain, changes are made in being and existence involving the whole human (Thompson, 2007). Important, mood may change elements or the totality of a human’s microidentity, which Varela (1992) explains is a readiness-for-action and its “corresponding lived situation a microworld” (p.). Varela (1992) introduces a flow of different microidentities and microworlds that change in the space of breakdowns of experience. The readiness-to-action of a microidentity changes with mood or emotion, and with consideration of having the experience of having a lived microworld. Should the changes of a negative emotion reflective of severe pain be conserved across microidentities that do not relate to one another, identity itself may be changed and conserved to be expressive of pain. As mentioned earlier, changes in identity are manifested in how the elements (more than those represented here) of identity relate to one another, are understood, ordered, addressed, and handled. Important to Maturana and Verden-Zöller (2008) are elements such as reflection, rationalization. thinking, reflecting, acting, hearing, and seeing, all of which change with mood, and the mood of severe pain will change them severely. Once pain moves from the sensory bare nerve endings of the nociceptors and affects the rest of the nervous system as a neuronal network, it is possible for identity held across being and existence to change and embrace severe pain. There is a movement from someone who has pain to someone who embraces pain, conscious or unconsciously, at the level of their identity that fundamentally changes who they are in a manner that expresses the experience of severe pain.

What emerges is an identity that is founded upon or embraces pain. Is it possible that a mood of severe pain worsens the severe pain itself? Perhaps the mood of pain sustains the perception of pain beyond the occurrence of pain itself?

Conclusion

Humans are disposed toward feeling pain. Their being is arranged in such a way that they have nociceptors distributed throughout the body. The pain can be severe, involving a noxious stimulus to the skin, soft organs, muscles, or joints. The distribution of nociceptors creates an enormous capacity to feel pain. It is unavoidable. Regardless of whether the state of nociceptors is triggered due to an internally generated nervous system change affecting the related bare nerve endings due to art or a memory, or a noxious stimulus. Being has many dispositions, one is toward pain. The ability to feel pain and the perception of pain itself are both intrinsic to humanness. As addressed in essay one, in athletes, existence is disclosed at its best through generating or distinguishing the pain that is within. Pain in the mind and self-consciousness are not discounted, and the pain can be as severe a tissue or organ damage, but it does not involve nociceptors and is therefore not a subject of this essay.

Maturana (1992) writes that his back does not ache until he distinguishes it. In cases of moderate to severe pain, Maturana’s (1992) use of distinctions is idealistic. For example, pain can become overwhelmingly severe and is experienced before it has been properly distinguished with a past denoting the source of he injury, the future of how long it will take to heal, what caused it, and what the properties are. Drawing this distinction may be forced, but the pain pre-existed distinguishing it.

One of the more menacing features of severe pain is its infiltration of identity that changes the existence and being of the human in pain. The integration of pain into identity is wicked and produces a human consumed with and defined by pain that changes the value, significance, and arrangement of the elements that constitute identity. Significantly, emotional changes toward more harsh moods or emotions that are conserved across time have a considerable influence over the dynamics of identity.

References

Armstrong, S. A., & Herr, M. J. (2022). Physiology, Nociception. In M. Abdelsattar, W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. S. Aeby, & S. E. Agadi (Eds.), StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

Dubin, A. E., & Patapoutian, A. (2010). Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 11(120), 3760–3772. doi:10.1172/JCI42843

Kendroud, S., Fitzgerald, L. A., Murray, I. V., & Hanna, A. (2022). Physiology, nociceptive pathways. In M. Abdelsattar, W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, & S. E. Agadi (Eds.), StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

Maturana, H. R. (1983). What is to see? Archivo de Biología y Medicina Experimentales, 16(3-4), 255-269.

Maturana, H. R. (1992, September 10). Explanations and Reality. Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Retrieved from https://www.hyperkommunikation.ch/texte/maturana_explanations.htm

Maturana, H. R., & Poerksen, B. (2011). From being to doing: The origins of the biology of cognition (2nd ed.). (W. K. Koeck, & A. R. Koeck, Trans.) Kaunas, Lithuania: Carl-Auer.

Maturana, H. R., & Verden-Zöller, G. (2008). The origin of humanness in the biology of love. (B. Pille, Ed.) Exeter, Devon, UK: Imprint Academic.

McMahon, S. B., & Snider, W. D. (1998). Tackling pain at the source: New ideas about nociceptors. Neron, 20, 629-632.

Mingers, J. (1995). Self-producing systems: Implications and applications of autopoiesis. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing.

Nachum, D. (2020). Chapter 6: Pain principles, section 2, sensory systems. Texas: Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy, The UT Medical School at Houston.

Norcliffe-Kaufmann, L., Axelrod, F. B., & Gutierrez, J. (2014). Pain, Autonomic Dysfunction and. In M. J. Aminoff, & R. B. Daroff (Eds.), Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences (Second ed., pp. 720-724). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Pinho-Ribeiro, F. A., Verri, W. A., & Chiu, I. M. (2016). Nociceptor sensory neuron-immune interactions in pain and inflammation. Trends Immunol., 38(1), 5-19.

Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.