The Issue of Common Existence Occluding the Nature of Being

The 60th Post on GregoryVig. An Essay on the Modes of Living of Existence and Being with an Examination of both. Inspired by a Reading of Biology and Philosophy. Vol. 1, Essay 1.

Introduction

This is a short essay examining two modes of living: existing and being, and the relationships between them (Maturana, Muñoz, & Ximena, 2016). Of the two modes, only existence can be lived exclusively; humans remain in it while living or more thoroughly dwelling in being (Heidegger, 1952). Existence is concerned with behavior, language, and having a mind, while being is the biology that enables existence to occur (Maturana, 1978; Maturana & Poerksen, 2011; Maturana & Varela, 1987). It is possible to interpret the discovery of being as a pathway to superior human experience and performance. This sentiment does not align with this paper’s expression, which is that being is ultimately a burden. It is a burden that may improve understanding of what it means “to be.” Such understanding may bring clarity and insight into the function and dynamics of humans and their humanness, but also frustration, grief, and anger, because being cannot be instructively or efficiently modified.

Existence

Existence is lived without the knowledge of biology, which is the understanding of being. At a minimum, existence involves behavior, including visceral, fine, and gross motor movements, as well as sensing that enables grasping, holding, turning, walking, balancing, and skills such as identifying objects and navigating complex situations with multiple moving variables. Existence is concerned with behavior and the experience of it, which involves having a mind, and a mind emerges through the biology of language and the social context in which it occurs (Maturana & Varela, 1987). Language is seen both biologically as being as a form of existence, that is added to existence here (Maturana & Poerksen, 2011). The mind, including self-consciousness, emerges through social behavior and has its own lived experience. The mind has a biological base, but through social behavior, it becomes a characteristic of the mode of living and a component of the ongoing, entire-body sense-making of existence. An understanding of being may arise from language and the mind, though more precisely, it occurs analytically from the perspective of existence to move being toward it. Beyond an analytical understanding, a body can be experientially lived in being, even while a portion of it remains in existence, which is necessarily a constant due to its concerns for behavior, language, and mind. Those who not only live but more deeply dwell in being, such as those in chronic and athletic-induced pain, experience the burden of the ordinary means of relating strongly to being.

Thus it is that the appearance of language in humans and of the whole social context in which it appears generates this (as far as we know) new phenomenon of mind and self-consciousness as mankind's most intimate experience (Maturana & Varela, 1987, p.233).

At the same time, as a phenomenon of languaging in the network of social and linguistic coupling, the mind is not something that is within my brain. Consciousness and mind belong to the realm of social coupling (Maturana & Varela, 1987, p.234).

As a human with a mind, behavior, and language, an act may be evaluated positively, negatively, neutrally, successfully, or unsuccessfully (Di Paolo, Buhrmann, & Barandiaran, 2017).

The experience of existence is based on the phenomenology of the experience of behavior, which may coincide with any of the following activities of the mind and language: notions, principles, frameworks, artistic or spiritual proclivities, inclinations, or other lived experiences, including moods, emotions, and feelings (Maturana, Muñoz, & Ximena, 2016). Engelland (2020) considers phenomenology to be the “experience of experience,” or, said another way, the experience of having the experience. For a redundant yet correct example, what is the experience of having the experiencing of living in existence in body, language and mind? It may be asked later, “What is the experience of the experience of existing as a body with an unknown biological being?” Engelland also writes, “Phenomenology potently combines these two forces in philosophy: search for the elusive essence of things and wonder concerning the possibility of experiencing things” (p.11). While the question of phenomenology is posed in this essay, later works may explore this question further.

Existence is quotidian, prosaic, unreflecting, everyday life, where there is no questioning of the living of existence or being as the source of its phenomenology because they are not thought of. An individual’s living in existence is never pondered or interrogated because it is lived successfully as the phenomenology of behavior, and a mind knows of that behavior and how to describe it in language, and as a mind has within it at any moment any other possible activity. Existence is a domain of lived experiences emphasizing behavior, language, and processes of the mind sufficient to navigate the world daily, for that is where humanity lives (Maturana, 1983). However, as will be discussed later, the phenomenology of daily life becomes that of being in athletics or chronic pain, where the being, the biology, of the human body starts to be revealed, even if lacking the language to bring it forth correctly.

Being

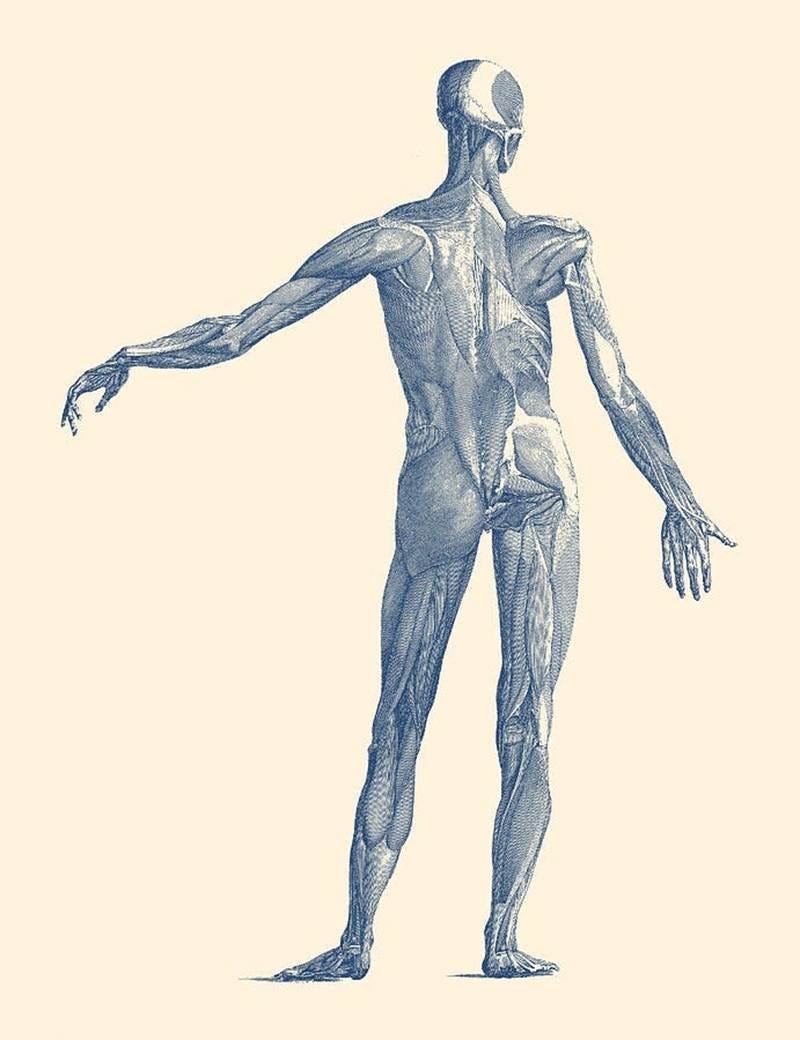

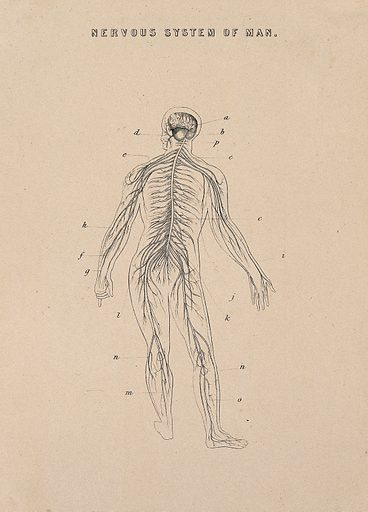

Existence understands behavior with the most significant concern, while being is concerned with the biology of the behavior. Biology is elevated to the level of being, as it is where the nervous and other systems operate, where internal changes first occur that enable the behaviors that are the focus of existence. Being is the more primordial mode of living, living through biology and the functioning of the body, which grants it the label of “being.” Existence is concerned with the lived experience of behavior, language, and having a mind, both are experienced functions made possible by biology. The human experience of living is in existence, but its being is in biology.

Being seeks to understand existence through studying the nervous system, which yields sensorimotor theory to grasp and apprehend behaviors occurring in the world. Being can call itself being because it understands what existence only experiences. The alignment between concerns of being and existence is what makes them what they are.

The essence of being is biological and takes longer to express than existence. It is presented here from the perspective of neurophysiology, the study of the nervous system. The nervous system includes sensory and motor surfaces, which are metacellulars of many sensory and motor cells. As these cells belong to the nervous system, they may be further specified as neurons. Sensory cells exist throughout the body, including the senses, and sense differently depending on their location. According to Frings (2019), sensory cells, in general, “Provide the central nervous system with vital information about the body and its environment” (n.p.). Sensory cells continuously monitor body posture, temperature, the objects in the environment, their movement and distance, digestive and cardiovascular system states, and the intake of oxygen and nutrients. A specific class of sensory cells evokes feelings of pain by avoiding potential causes of irritation or injury. In connection with sensory surface perturbations, motor surface responses may range from “twitching of the skin to violent startle responses” (Frings, 2019, n.p.).

Research indicates that recurrent relationships between sensor and motor surfaces, called “sensorimotor,” motivate conceptual and rational thought, decision-making, language, mental imagery, and other complex cognitive acts. While it may seem as if the sensorimotor activity directly animates the human, sensorimotor activity and the neuronal network of which sensory and motor surfaces are a part do not intersect with human behaviors out in the world, nor are they deducible from one another. One cannot examine sensorimotor activity and deduce from it abstract worldly behaviors, nor can sensorimotor activity be inferred from behavior in the world. Much of this is attributable to the fact that the nervous system, as a network of neuronal elements, is closed (Baeza-Florez, 2022; Maturana & Varela, 1984).

Despite revealing itself to the world with sensory surfaces, these surfaces are only perturbed by stimuli. Stimuli do not determine what reactions sensory surfaces produce through their connection to the rest of the nervous system, including motor surfaces and neurons. There is no natural affordance for external stimuli to determine what happens within a human. The nervous system’s structure determines the sensorimotor response when it is perturbed and what state the neuronal network will adopt. What a human does is not a matter of what stimuli are presented to them but how the entirety of the nervous system is structured when it happens. The internal correlations and state of the nervous system following a perturbation, stimuli, are of the network’s own devices. It should also be noted that the nervous system can also change states entirely internally and continuously without perturbation. Whether from perturbation or internal activity, the nervous system is constantly changing states. As a matter for later essays, the phenomenology of having the mode of living of being may be explored (Di Paolo, Buhrmann, & Barandiaran, 2017; Varela, 1992; Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1993).

The Tragedy of Existence

Humans and non-human animals alike live in existence. That is where they live, and that is where they exist (Maturana, 1983). In the domain of behavior are bodily sense-making, language, deciding, thought, hiking, climbing, behavior, through motor and sensory activity, skills, mastery, including running, jogging, walking, picking objects up and putting them down, navigating uneven surfaces with their inclines, declines, and dynamic situations (Di Paolo, Buhrmann, & Barandiaran, 2017; Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1993)

Existence is lived in successfully but without the knowledge of being. The movement of being toward existence or vice versa may be to the benefit of comprehending one’s learning, action, higher cognitive functions, and movement through life, which is to say, living. The true tragedy of being is its lack of relation to existence. Without being, there is a blindness to the complex biology from which the behavior, language, and mind emerge, and a focus on existence. Still, the most lamentable aspect is that existence, not knowing being, is necessarily always present alongside it. The deep, and yet at the same time superficial foundation of knowing of existence produces a shallow understanding of humanness by oneself. Conceiving of being is to understand existence truly, yet existence is not dissolved through its knowledge of being. Existence and being remain non-interacting and non-deducible. However, knowledge of one still enriches the other. Understanding existence from the perspective of being grounds behaviors in biology and naturalizes them, explaining the manner and phenomenology of behavior. Existence becoming aware of being does not make existence a mirror of being. Instead, existence becomes being-informed behavior that can relate to the deep substructure of being to inform living in existence and provide understanding.

In an instance of existence ultimately void of any sense of being, humans are flying a plane without knowing how flight is possible. Humans entrapped in the mode of living are unaware that many mistakes, successes, learning processes, movements, and the navigation of life are embedded in sensorimotor activity, and the cognition they have confined to the skull is distributed throughout the entire body. It is possible to involve sensorimotor structures in love, as love is an emotion, and emotions affect the whole body, including how humans act. Of course, humans and other animals have long thrived in existence. The question posed here is whether relating being to existence, where humans act, learn, and think in the world, would have discernable benefits, and it is put forth on beings’ merit that existence should have an awareness of it.

Übermensch

To begin, in the words of the original text, Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra (1969), “I teach you the Superman. Man is something that should be overcome. What have you done to overcome? All creatures hitherto have created something beyond themselves: and do you want to be the ebb of this great tide, and return to the animals rather than overcome man?” (p.41). In the previous source material, “Übermensch” is translated as “Superman.” Wanyama (2024) writes that Nietzsche questions, “How can your life, the individual life, receive the highest value, the deepest significance? How can it be least squandered?” (p.11). Wanyama (2024) continues with Nietzsche’s response: “ Certainly only by living for the good of the rarest and most valuable exemplars and not for the good of the majority, that is to say, those who, taken individually, are the least valuable exemplars. Nietzsche calls the exemplars ‘the rarest and most valuable.’” (p.11). Wanyama (2024) discusses Nietzsche and explains that the exemplars are not individual, unique humans, but a type, like Übermensch, that humans strive to be by first asking the earlier questions. The Übermensch is presented “as the ‘inducer,’ to become what one is, such an ethical task is individually determined” (Wanyama, 2024, p.11).

“Through the type Übermensch, Nietzsche envisions how the individuals could be induced to singular individuality through perpetual overcoming….The type Übermensch as the exemplary figure stands above drawing individuals onward and upward through self-overcoming to singular individuality. That overcoming demands espousing a basic drive to a life as the will to power” (p.12). Later, Wanyama (2024) makes two connections: “Übermensch and the singular individual is grounded in Nietzsche’s notion of will to power as overcoming and form-giving (discipline and generative power” (p.47).

It is held here that the answer to Nietzsche’s questions is to seek deeper meaning in one’s lived in existence, which, within the correct parameters, may lead to being. With being uncovered, and lived in or analyzed, there is an ongoing but never complete overcoming of existence to define being and give it form. Übermensch is evoked here as an exemplar, as a type to strive for by pursuing an ideal model of a human who, context permitting, may discover the life significance of understanding existence’s relationship with being and being’s connection with existence.

Übermensch in Pain

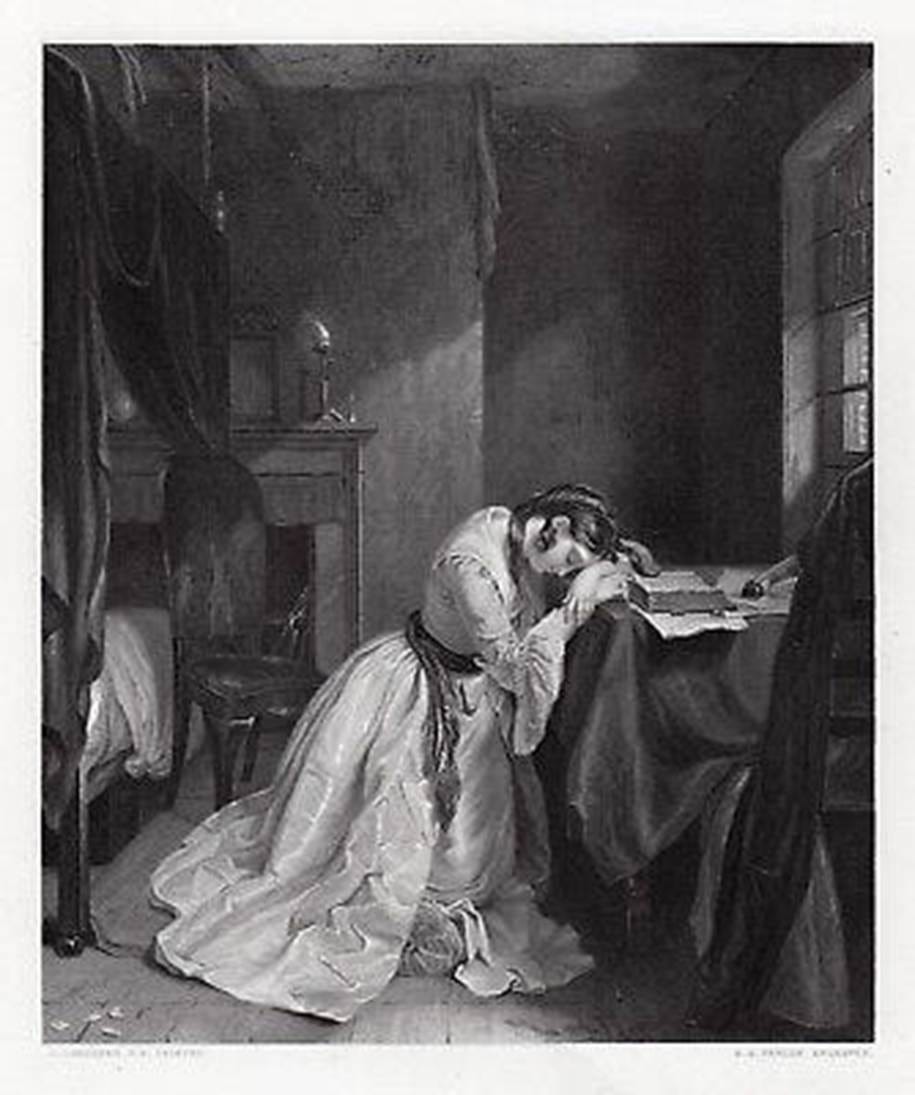

It is argued that the athlete, particularly the long-duration high-intensity athlete, may be acutely aware of different relationships between sensing physical pain throughout their sensorium, labored breathing, a lack of nutrients, high heart rate, and muscle activation, fatigue, or cramping. The emotion of aggression and its denial of self may prevail, and in this case, the athlete will continue pushing forward. There may also be acceptance of the current state of affairs, leading to maintaining their performance or decreasing effort. The athlete is keenly aware of the movement of their body at the point of their performance, where discomfort or pain correlates to muscle weakness, discoordination, or pain. As muscle pain, respiration, and cardiovascular rates increase and are sensed by humans, performance eventually and involuntarily decreases, given a long enough time frame. Being is a burden. The relationships among these variables in the sensory surface and motor surface groups may become apparent, even when not distinguished in that manner, and still be experienced as being by the athlete.

The human in chronic pain and the athlete are similar to Nietzsche’s Übermensch in the context of being an exemplar in that they are the most attuned to existence, its behavior, language, and biological being, and they are continuously overcoming themselves to strive to be in touch with being. The athlete in pain and the human regretfully in chronic pain dwell more in being than in existence. For the athlete, it is purposeful; they compete and train and voluntarily dwell in biology, and the athlete relates to being by pain, which lays being bare, and the experience is eventually positive. Dwelling, as used here, as it appears in the following: “Dwelling itself is always a staying with things” (Heidegger, 1951, p. 353). For the athlete, dwelling may be more than staying with things, which the in the context of a human with chronic pain, may be involuntary. Dwelling is also related to building, such as in the case of temples and ships, but also to act with care and tend to living things, “Both modes of building - building as cultivating…and building as the raising of edifices…are comprised within genuine building, that is dwelling” (Heidegger, 1951, p. 353). The athlete, particularly the coached athlete, attends to their training that reveals being (even if not distinguished) with the care of a coach, doctors, and heart rate and power meters, and they become aware of their present limitations and how they will overcome them in the future. This is a process of cultivation. The athlete also builds and refines sensorimotor schemes, metabolic and cardiovascular capacity, which they would not otherwise have. While dwelling in being during competition, they eat the fruits they have been cultivating on the vine (Heidegger, 1951). The cultivation of being and existence that can run a one-hundred-mile footrace leads to the building of an athletic career complete with podium finishes, prize money, name recognition, and advancing through the categories. The athlete builds from what has been cultivated (Heidegger, 1951).

A human in chronic pain is dragged into dwelling in being, and their experience is negative. Humans with a condition that produces chronic pain do not wish to be aware of their being. They may take medication to relieve themselves of their being’s chronic pain and live in pure existence that does not know being. Through pain, their awareness of being, moving, and sensing becomes regretfully apparent. A human in chronic pain becomes constantly aware of the issue, such as a disease, injury, or failed surgery, for example, which keeps them in chronic pain, which arises through being and inhabits existence. Differentiated from athletic pain, chronic pain is not a sign of successfully pushing a boundary or achieving a higher level of fitness. The phenomenology of chronic pain is that of trying to escape one’s shadow. The pain is always there, and the sufferer remains aware of their pain and their own damaged being. Being is a burden.

Both humans in pain are aware there is something more than the flow of everyday life that, in some cases, is forgotten before the memory can form. Pain that reveals being can elongate time, attach to self-perpetuating identity, and change emotional range. There are consequences to pain as the catalyst for realizing being, though it remains the shortest route from living purely in existence to living partially, if not dominantly, in being. Being can inform existence, and existence, to a much lesser degree, may relate to and inform being. In this essay, pain and analysis have been presented as ways of living within or live with building, as is the case with the analytical. More ways of living with building may be imagined in later essays.

Conclusion

Being is distinct from existence and much more of a concrete essence than articulating joints, moving limbs, speaking, and operating with a mind in existence. The presence of a mind in existence would make it seem like the actual state of being. However, the mind emerges through the biology of language and social life, which involves behavior. It is also critical to self-consciousness, interacting with cognitive states, and having the experience of the lived experience of having a mind, language, and behavior without the recognition of having a being, an enormously complex biology.

Being is biological. It arises from the structures, surfaces, and processes that make human existence possible. However, due to the nature of the nervous system, the biology of being does not intersect with existence, and behaviors in the world do not intersect linearly with subsequent behaviors. However, without biology, there would be nothing that is called behavior. Sensorimotor theory, in particular, demonstrates how mind, language, and body are intertwined but not directly causal, which is at the center of being. Being in this sense, does not endeavor to address an existential problem but examine and mend its disconnection from existence.

References

Baeza-Florez, M. (2022). Humberto Maturana: Biology of knowing for beginners. Independently published.

Di Paolo, E., Buhrmann, T., & Barandiaran, X. E. (2017). Sensorimotor Life: An Enactive Proposal. Oxford, UK: Oxford.

Engelland, C. (2020). Phenomenology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Frings, S. (2009). Primary processes in sensory cells: current advances. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 1-19. doi:doi 10.1007/s00359-008-0389-0

Heidegger, M. (1951). Building Dwelling Thinking. In D. F. Krell (Ed.), Basic writings: Revised & Expanded edition. Ten key essays, plus the introduction to BEING AND TIME (pp. 343-365). San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco.

Maturana, H. R. (1978). Biology of language: The epistemology of reality. In G. Miller, & E. Lenneberg (Eds.), Psychology and boilogy of language and thought: Essays in honor of Eric Lenneberg, (pp. 27-64).

Maturana, H. R. (1983). What is to see? Archivo de Biología y Medicina Experimentales, 16(3-4), 255-269.

Maturana, H. R., & Poerksen, B. (2011). From being to doing: The origins of the biology of cognition (2nd ed.). (W. K. Koeck, & A. R. Koeck, Trans.) Kaunas, Lithuania: Carl-Auer.

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1987). The tree of knowledge. Boston, MA: New Science Library.

Maturana, H. R., Muñoz, S. R., & Ximena , D. Y. (2016). Cultural-Biology: Systemic consequences of our evolutionary natural drift as molecular autopoietic systems. Foundations of Science, 21, 631-678.

Nietzsche, F. (1969). Thus Spake Zarathustra. London: Penguin Books.

Varela, F. J. (1992). Ethical know-how: Action, wisdom, and cognition. (T. Lenoir, & H. U. Gumbrecht, Eds.) Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1993). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wanyama , A. M. (2024). Nietzsche on individual autopoiesis: Critical dialogue with ethno-philosophy of shienyu ni shienyu and sosmopoeisis. Berlin GmbH, DE: Logos Verlag.