Trivariate Relationships in Organizational Change

Introduction

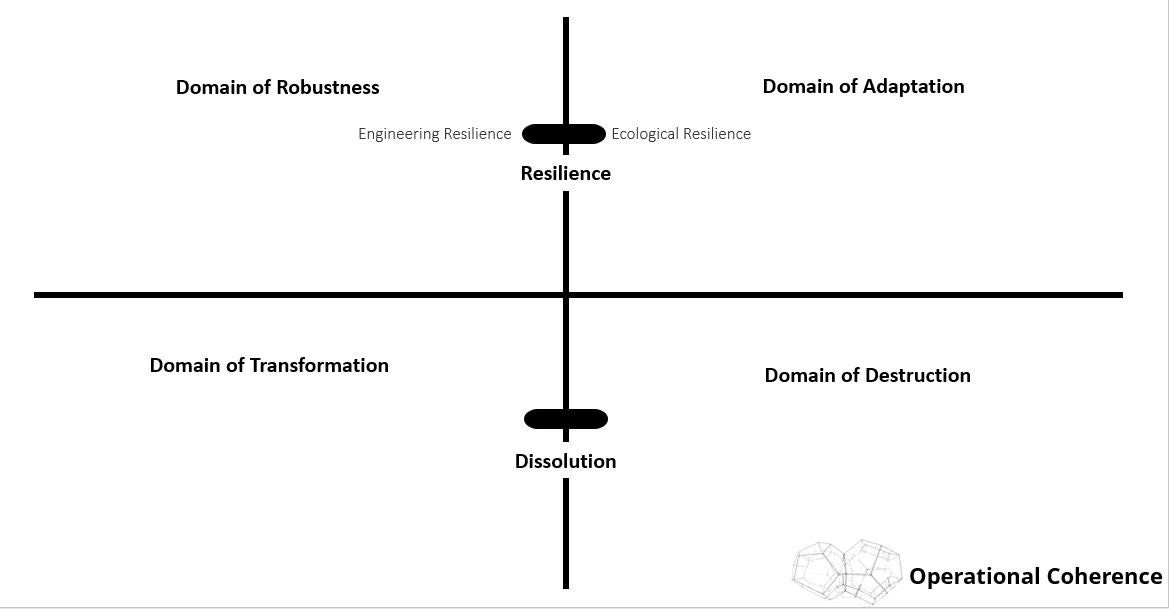

Below is a matrix focused on organizational change I have been developing over the past year or so. I introduced it in this blog post , lectured on it in this presentation , and then wrote about it here and here. It has appeared in two other presentations and will soon be presented as a tool in my upcoming talk at the Colorado Emergency Management Conference entitled "Who we are and Who we want to be: A Look at Organizational Change." I wanted to post an update and introduce it again in a more succinct post prior to the upcoming conference. It remains in a fluid state, and I am thoroughly enjoying the process of moving it along.

Theoretical Roots

The matrix has evolved through several versions influenced primarily by the evolution of my own thinking and the act of explaining it to others. First and foremost, this tool finds its roots in Humberto Maturana's concept of structural determinism (Maturana, 1983). A sufficient understanding of structural determinism contains two key ideas. The first is represented by the question, "How much can something change and stay the same?" As well as its inverse, "How much can something change before it is no longer the same?"

The second and most important idea of structural determinism is that events such as incidents do not determine organizational responses. All events can do is trigger, but not determine, how an organization is affected by an event. Instead of there being an assumed direct causal link between events and organizational responses, the way the organization exists at the moment it is perturbed by the event is the deciding variable in how the organization will respond both internally and externally (Capra & Luisi, 2014; Maturana, 1988). Proposed here is a move away from assuming a bivariate relationship among events and organizational responses to a trivariate relationship where events, the organization's identity when the event occurs, and the responses the event triggered are all considered, with emphasis placed on organizational identity (Donaldson, 2001). This core notion of structural determinism is echoed in Donaldson's writings on the contingency theory of organizations.

At the most abstract level, the contingency approach says that the effect of one variable on another depends upon some third variable, W. Thus the effect of X on Y when W is low differs from the effect of X on Y when W is high. For example, it might be that when W is low, X has a positive effect on Y, whereas when W is high, X has a negative effect on Y. Thus we cannot state what the effect of X on Y is, without knowing whether W is low or high, that is, the value of the variable W. There is no valid bivariate relationship between X and Y that can be stated. The relationship between X and Y is part of a larger causal system involving the third variable, W, so that the valid generalization takes the form of a trivariate relationship (Donaldson, 2001, pp.5-6).

In the present context, X is an event and Y is an organization's response to that event. If a bivariate relationship is assumed, the event has a direct effect on the response (Y). In a trivariate relationship, X and Y are separated by W, the organization's identity when X takes place. The idea of W is expressed in the term "organizational identity" throughout the following. Variables such as robustness, resilience, adaptive and transformative capacity, management and leadership styles and structures, available information, inflows of materials and outflows of products and services, and relationships between the organization's social and technical elements, are all part of W and shape the response the event will have. Different elements belonging to W can be looked at as being valued high or low like in the above from Donaldson (2001) at the time the event takes place (e.g., resilience was high or low according to some metric).

Influence

Since the beginning of this matrix, I have been open with the influence I have drawn from the Cynefin Framework. In particular, the boundaries between the domains being gradients and the dynamics of moving among the domains (Kurtz & Snowden, 2003). This influence remains and is visible in the matrix above and in the updated version below. It was while reading back and forth from Maturana and Cynefin articles and blog posts that the connection between the matrix I am developing came into being. This is only one of the areas where the two narratives complement each other.

In use

In practice, each domain of this matrix will be populated with anticipated events whether they be external to the organization such as a hazard event or internal to it such as an organizational change initiative, changing in staffing, an internal incident such as a software outage a new policy, etc. The purpose of the matrix is to get all involved to think prospectively about the events they may encounter over a certain time span and then link those events to the type of responses they may trigger by considering the role of present and future organizational states. The third step is to prepare to respond and consider how organizational dynamics can be changed to shift events from the domains of greater energy expenditure and uncertainty in the bottom of the matrix towards the top left. The questions here are many and include, "What is out there and how will we respond to it?" "How can we change the effect these events will trigger in the future?"

Domain of Robustness: Events in this domain generally do not trigger a change within the organization due to energy already spent fortifying the present state. If they do trigger a change, responses will be in the form of small disruptions experienced as temporary interruptions before a return to normalcy. The identity of the organization is unperturbed (Di Paolo, et al., 2017).

Domain of Adaption: Events in this domain trigger changes in how the organization maintains its identity, but not what its identity is. Possible changes fall into three categories: Changes in what is brought into the organization to make products and/or services, changes to how the social and technical elements of the organization interact to produce products and/or services, and finally changes to what products and/or services the organization creates. The driving question in the domain of adaptation is "How much can things change and still stay the same?" Changes are made to how the identity is reproduced but not the identity itself. Identity is static while all the elements and actions that produce it are dynamic (Maturana & Poerksen, 2011).

Domain of Transformation: The domain of transformation is where all events that could trigger a change in organizational identity belong. An organization may enter intentionally or unintentionally (Folke, et al., 2010). Here, both identity and how it is reproduced become fluid. A new identity may emerge with or without traces of the old one held within it, such as continuing to operate as an emergency management entity but with new products and services, diversified membership, and a new conception of value (Maturana & Verden-Zöller, 2008). The central question here is "How much can we change before we are no longer the same?" Change that exceeds an organization's adaptive capacity to keep an identity constant moves into the domain of transformation where a new one appears, or it falls into the domain of destruction. Key is the rate at which an organization can reinvent itself.

Domain of Destruction: Events in the domain of destruction trigger complete breakdowns in the organization's ability to function. As the organization enters this domain it loses its capacity to reproduce an identity. The organization finds itself in a riptide. If inhabited for too long, events in the domain of destruction can trigger unrecoverable responses within an organization to the extent that the organization no longer exists (Maturana & Varela, 1987).

New Spaces

Since its last presentation at the Northern European Emergency and Disaster Studies Conference, I have added in these two in-between spaces that are influenced by Cynefin's liminal zones but specific to organizational change. What I am intending to express along the vertical axis is the presence of zones between the domains where an organization has not yet left the domain and not quite entered the other, but the dynamics of the response have changed.

Moving from the domain of robustness to the domain of adaptation, there is the graded zone of resilience broken into two areas: Engineering resilience and ecosystem resilience. Moving from robustness to adaptation, organizations first respond to increasing pressure from an event or events by working to recover the organization's state prior to the disturbance through an engineering resilience approach. As events begin to necessitate more of an adaptive response and less than one focused on recovering a previous state of affairs that may be outmoded, the organization begins to move into the area of ecosystem resilience where new norms and forms are necessary (Holling & Gundseron, 2002). The resilient zone provides a space for understanding organizational dynamics that do not fit squarely in the domain of robustness or in the domain of adaptation. In the lower half of the matrix, the zone of dissolution accomplishes the same end.

The dissolution space at present is an undivided graded area that spans the domain of transformation and the domain of destruction. Operated within in the domain of transformation, dissolution can be a constructive component of creating a new identity and a means to reproduce it. Here old structures are being removed as new ones take their place. The organization as it used to exist dissolves as something new begins to emerge. Moving across the boundary between transformation and destruction, dissolution can be a temporary state of being overwhelmed where identity and the means to reproduce it break down. This side of the dissolution space is inhabited only by accident and is not meant to be inhabited for extended periods of time as this runs the risk of moving into the domain of destruction. Organizations existing in the destruction domain side of dissolution will have the experience of moving towards its riptide but not quite in it while feeling pressure from various sources.

Closing Thoughts

I recently wrote a post titled "An Audible Longing for Theory." In it I discussed a discovered openness to theory provided it can be readily integrated into practice. At this point, I think this matrix has moved closer to being immediately usable. However, it continues to need engagement with an emergency management audience to further contextualize the domains and the dynamics among them.

References

Capra, F., & Luisi, P. L. (2014). The systems view of life: A unifying vision. Padstow, England: Cambridge University Press.

Di Paolo, E., Buhrmann, T., & Barandiaran, X. E. (2017). Sensorimotor Life: An Enactive Proposal. Oxford, UK: Oxford.

Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organization. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T., & Rockström, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society, 15(4). Retrieved from www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/

Holling, C. S., & Gunderson, L. H. (2002). Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Washington D.C.: Island Press.

Kurtz, C. F., & Snowden, D. J. (2003). The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated. IBM Systems Journal, 42(3), 462-483.

Maturana, H. R. (1983). What is to see? Archivo de Biología y Medicina Experimentales, 16(3-4), 255-269.

Maturana, H. R. (1988). Ontology of Observing: The biological foundations of self-consciousness and of the physical domain of existence. Texts in Cybernetic Theory: An in- depth exploration of the thought of Humberto Maturana, William T. Powers, and Ernst von Glasersfeld (pp. 4-53). Felton, CA: American Society for Cybernetics.

Maturana, H. R., & Poerksen, B. (2011). From being to doing: The origins of the biology of cognition (2nd ed.). (W. K. Koeck, & A. R. Koeck, Trans.) Kaunas, Lithuania: Carl-Auer.

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1987). The tree of knowledge. Boston, Massachusetts : New Science Library.

Maturana, H. R., & Verden-Zöller, G. (2008). The origin of humanness in the biology of love. (B. Pille, Ed.) Exeter, Devon, UK: Imprint Academic.