Stories for Designing in Emergency Management

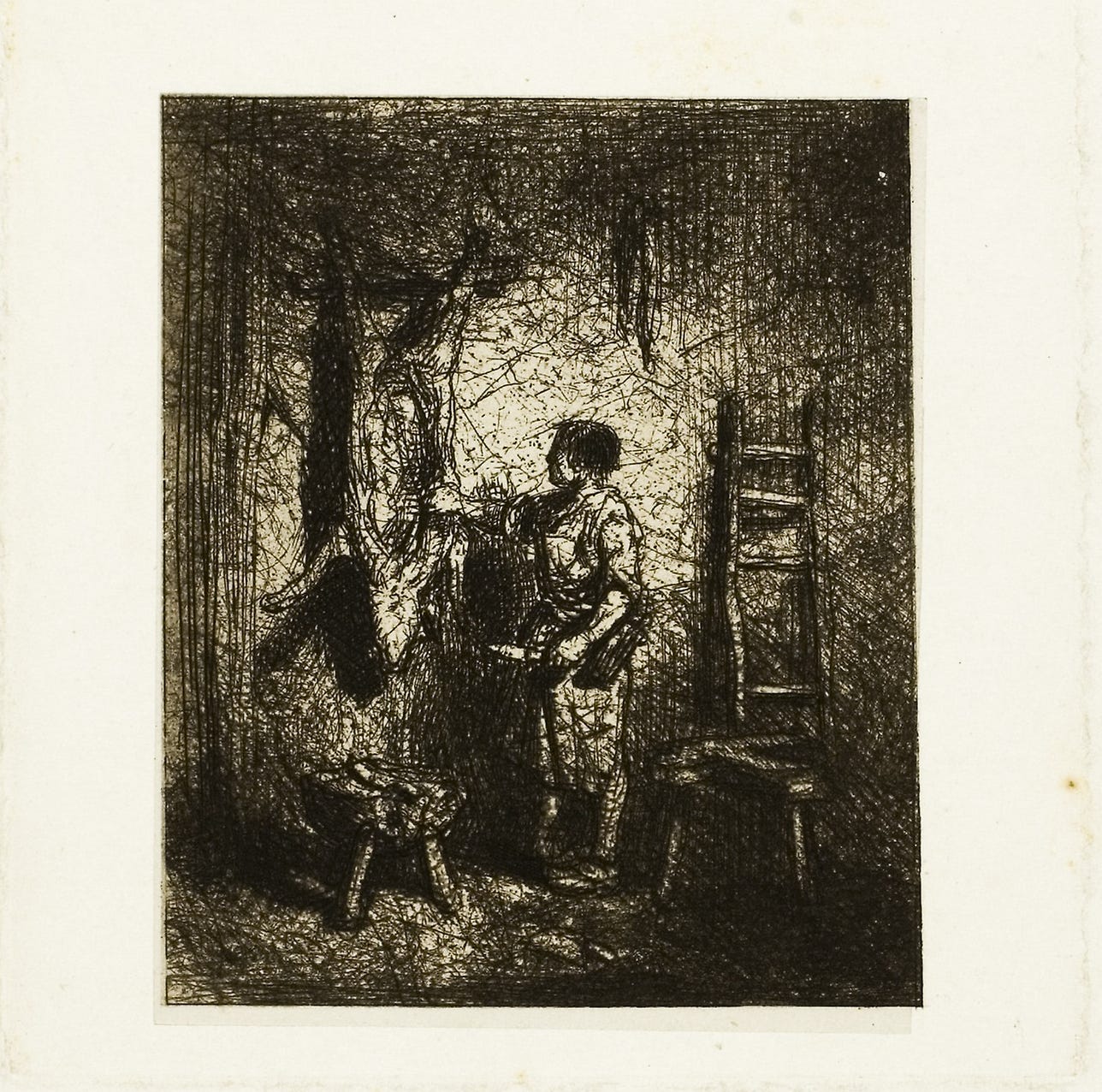

Design for Emergency Management With Narrative as a Substrate. The Butcher, the World, and the Symphony. A NoiseBox Publication.

Introduction

I was delivering my annual talk at the Colorado Emergency Management Conference in February of 2020. At this time, COVID-19 was located in the Pacific Northwest, and there seemed to be a sense of safety given its location. Or, there was no perceived imminent threat to Colorado, at least there was not in the conversations I participated in. The talk I delivered was titled “Design Thinking for the End of the World.” It revolved around a few key points, the central of which was the stories we tell are how we make sense of the world so that we may design for it. Typically, I share the design process with emergency managers by componentizing it into two interrelated phases: Crafting a desirable and foreseeable end and acting intentionally to bring it into being. They can be broken down much further, as needed. During this talk, the design process was broken down into three components.