"To Live to Survive, to Survive to Live."

Cassette Series Number 7, "Survival." Title by Edgar Morin. A Speculative Look Ahead.

Preface

The purpose of this essay is to explore social processes in transitory survival-focused groups that unify purely for survival, then disperse, and are speculated to be of growing importance from now into the future. This essay is concerned with how they are possible. The exploration of these groups first focuses on theory building and then situating the theory in the narrative of an emergency.

This essay is the seventh installment of the cassette series. The cassette series celebrates the influence of music on the writing process and the “Do it Yourself” style of the blog format that resonates with cassette culture. A link exists between music and writing that is powerful and meaningful, and becomes part of the process. Like other installments of the cassette series and other recent writings, the objective is to write essays or chapter-length pieces to allow for greater complexity and more room to unpack the subject.

Introduction

In the cassette series, tapes four, the white tape, and five, the black tape, looked ahead fifty years and imagined what life could be like from social, economic, and ecological perspectives. Both tapes focused heavily on natural hazards, how they may worsen over time, and what the human experience of increasing hazard disruption frequency and severity would be. Tape number four makes dystopian speculations founded on data, while tape number five draws from the experience of the author, defined possibilities, and the platform established by its predecessor. Both tapes concluded with the exodus of a population. Tape number four expands this point further and discusses a diaspora from Arizona leading to the resurgence of ghost towns to escape often deadly heat and regular mass disruptions caused by natural hazard events. Both tapes four and five set important precedents for tape number seven, which discusses survival in the period from 2074 to 2124, in which it is assumed most lives will be concerned with surviving either continuously or periodically.

The focus of surviving is social, in particular, the small, transitory social group. While many of the social dynamics are based on the literature, the reader should be reminded that looking ahead from where the earlier tapes left off is speculative dystopian fiction to fill in the unknowables and their experience.

Community

If warming and catastrophic trends continue, living between 2074, as described in tapes four and five, and 2124 will likely be a harrowing experience dominated by scarcity, suffering, fear, struggle, and survival. By the time the phone calendars turn to “2100,” the United States landscape will likely have transitioned markedly through many “states,” where the prevailing season is now “heat and disaster,” more so than previously imagined. The sports industry, particularly snow sports, has become nothing but a memory. During the majority of the year, other outdoor sports, including climbing, running, cycling, hiking, basketball, baseball, tennis, and track and field, are unsafe due to hot temperatures. Due to the extremity and uncertainty of the weather, series competitions are impractical. The decline and then disappearance of 2025 normative athletics at (and very likely much before) the turn of the century began to change the social landscape as physical interactions decreased. From 2074 onward, the expansion and intensity of the heat and disaster season had already started changing the social order by dividing it into families and individuals who could no longer rely on the outdoors for physical interactions. They now had very limited opportunities for enjoying time together and engaging in in-person social activities that build up social process, meaning the development of socialness among or between people. Going to the movies, large-scale and multi-purpose indoor athletic facilities enable community members to continue engaging physically and socially in the place of outdoor activities, though not with the same draw or capacities.

As discussed in tape number 4, being online indoors to stay protected from the heat and engaging with friends through likes, comments, and video chats and clips allows community members to engage in virtual interactions and maintain some resemblance of community and social process. Virtual interaction cannot wholly take the place of physical social interaction. Physical interactions provide a superior space for the temporal processes of structural coupling, where a congruence among individuals and their environment appears over time, forming social process (Maturana & Varela, 1987). In a physical environment, structural coupling is aided by the ability of the group to interact with one another’s emotional states, smelling, touching, and hearing one another (Maturana & Verden-Zöller, 2008). Proximity contributes richly to structural coupling and, in turn, is involved in building cohesive, coherent, and resilient social groups. As noted already, structural coupling is a temporal process, and as such, it requires time to form mutual congruence among group members and the environment. How much time will there be for structural coupling in the presence of upheaval from more severe heat and disasters, political and economic instability, and the introduction of new technologies? How will the temporal forming of mutual congruence underlying social process involved with survival take place when there is no time for it to? This important question of congruence, or synchrony, in the context of survival is addressed later, though not at the relational depth of structural coupling.

Calamity

In the decades past 2074, it indeed continued to get hotter, and disasters became more frequent and severe. However, this was not all. There was an increasingly hostile environment at home and around the globe caused by divisive politics, politicians perpetually unsure about what action to take against the rising tide of calamity, primordial arguments over what is real and causally related, and what is not, and what the appropriate social order is. As apparent as these divisions are in the present day, in 2100, they have grown wildly in intensity and severity and become more visible and electrified. Divisions can no longer be ignored or circumvented; there are too many, and too large, like towering cliffscapes that violently fragment society. The ongoing division is amplified by a world that is too hot, the routine loss of property from disaster, constant uncertainty, and disagreements over politics and religion, all leading to regular violence (Keen, 2008). In almost all cases, political enmity mixed with other grievances following a disaster, as expected, made response and recovery more difficult and dangerous.

In 2100, homes were constantly being lost to hazards such as wildfires, and depending on terrain, homes that were not lost to wildfires were often lost to the mass land movements that followed. Other hazards, such as hurricanes and intensified winds, became more frequent and deadly and destroyed increasingly more homes and structures, like wildfires, leaving communities without utilities for extended periods, leading to another variety of outrage. Heat, droughts, heatwaves, tornadoes, wind events, hurricanes, wildfires, outrage over the economic and political system, repeated government shortfalls, disaster response and recovery, food prices, resource scarcity, supply chain breakdowns, and a lost national identity have made the country volatile and threatening. In varying degrees of materiality and frequency, enormous swaths of the country are concerned with survival.

A Theory of Transitory Survival Groups

Of those whose lives consist of regular survival, there are three main archetypes. There is the independent survivalist, the transitory survival group, and, uncharacteristic for the times, stable communities formed for survival purposes. The independent survivalist and stable groups are not presently of interest, while groups formed out of the need to survive a certain situation are. These groups are predicated on the rapid establishment of social process and have the potential benefits of increased safety, collaboration, cooperation, and combining resources.

Quickly converging social groups are essential to survival in the far future as individuals live in a world of danger, upheaval, instability, and quick materializing disruptive events with natural and social sources. Groups that form for the purpose of surviving certain circumstances only exist as long as the circumstances persist. Much less likely, they may become or join stable groups, but that is beyond the scope of this essay. Social process needs to be established urgently, and naturally, the common bond of a shared purpose is important but insufficient (Maturana & Varela, 1987).

There are three key elements involved in establishing a theory of transitory survival groups: Phase locking, the legitimacy of the other, and consensuality.

Phase Locking

Phase locking is the first element of the theory of transitory survival groups and provides a different perspective than the more normative structural coupling to explain the forming of social process. This biological phenomenon of phase locking is defined below in two quotes.

More generally, phase locking refers to the ability of a neuron to synchronize or follow the temporal structure of a sound” (American Psychological Association, 2025).

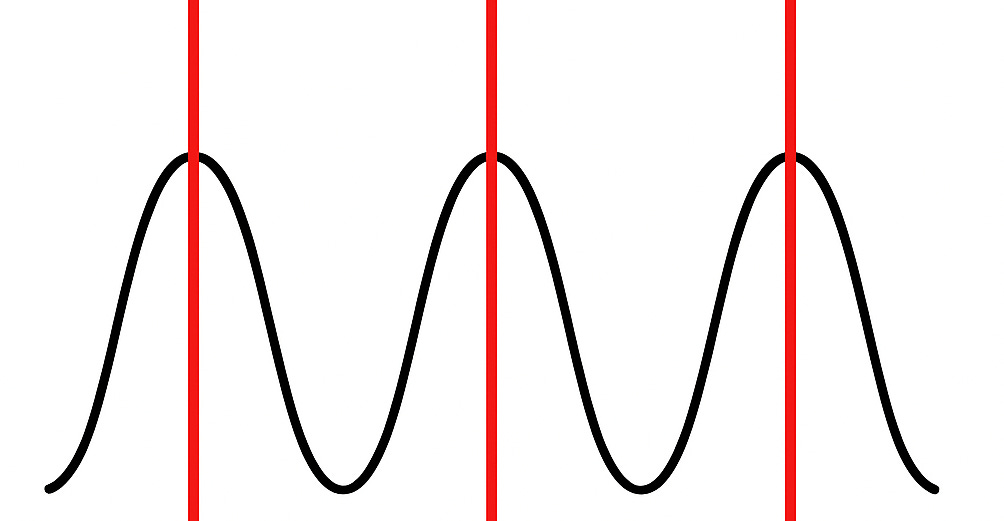

Recordings made from neurons in the auditory phase locking, the consistent firing of a cell at the same phase of a sound wave (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2007, p. 367).

Phase locking occurs when a group of neurons or neuron fire at the same time, along the same place in the structure of a sound, as pictured above. As such, part of the nervous system has become synchronized with something external to it, similar to structural coupling’s “congruence” (Maturana & Varela, 1987; Thompson, 2007). However, it does not appear that phase locking involves the same duration as structural coupling to produce congruence or the same depth of meaning.

Structural Coupling: We speak of structural coupling whenever there is a history of recurrent interactions leading to the structural congruence between two (or more) systems (Maturana & Varela, 1987, p.75).

Further, in the auditory context, phase locking involves temporality and the localization of sounds. Below, phase locking is presented as one of the vital elements involved in temporal encoding, which is the way the auditory nerve conveys the timing information of sound stimuli, localizes sounds in space, and is involved in understanding speech. Healey (2005) notes that in the case of lower frequency sounds below one to two kHz, “nerve fibers can fire in synchrony with the peaks of the sound wave [as pictured above]. This allows the brain to track the timing of the sound precisely. Above a certain frequency (typically around 1-2 kHz), individual fibers can no longer fire in synchrony with every cycle of the sound wave” (n.p.).

Temporal encoding refers to the way the auditory nerve represents the timing of sounds. This is crucial for perceiving rapidly changing sounds, such as speech, and for localizing sounds in space. One of the key mechanisms for temporal encoding is phase locking, where auditory nerve fibers tend to fire at a specific phase of the sound wave (Healey, 2025, n.p.).

Compared to structural coupling, phase locking happens readily. In the words of Healey (2005), “this is crucial for rapidly changing sounds” (n.p.) in reference to phase locking’s temporal encoding. Phase locking between speech and the environment and the auditory nerve is not the only type of phase locking taking place.

Receptors in the skin are also capable of phase locking. The skin has two types of mechanoreceptors sensitive to vibrations: pressure receptors situated deep within the skin and touch receptors closer to the surface of the skin. Pressure receptors (Pacinian corpuscles) “are rapidly adapting and are present in the deeper layers of skin, ligaments, and joints where their function is to detect high-frequency vibration and deep pressure” (Bajwa & Yasir, 2025, n.p.). Touch receptors (Meissner’s corpuscles) “detect low-frequency vibration and are present in glabrous (smooth, hairless) skin on fingertips and eyelids” (Bajwa & Yasir, 2025, n.p.). The research indicates that both receptors can also phase lock to vibrations, but point strongly to Pacinian corpuscles (Turecek & Ginty, 2024). There is, then, a massive field in which phase locking can take place in the present without the time being tied to effectiveness, and involves a biological response triggered by environmental stimuli wherein nerve cells fire in synchrony with the stimuli and can rapidly change.

Phase Locking in Social Process

Phase locking, as it is explained biologically, lacks social significance. The task now is to make phase locking, a biological concept, intelligible within social process, particularly that of transitory groups formed for survival. Applied socially, phase locking refers to synchrony among a rapidly forming group of people and their environment for survival purposes, enabled by a multitude of neurons firing at the same time at the peaks of the vibrations emitted by members of the group including hearing the other members, feeling them, and hearing and sensing their surroundings through the skin and ear, temporally encoding the stimuli perturbing the auditory nerve and localizing it in space.

In short, in the survivability context of transitory groups, phase locking refers to the local and spatial synchronization of group members with each other and their environment through biological processes in the auditory nerve and at different layers in the skin, ligaments, and joints. This synchronization is the sub-foundation of social process.

The Legitimacy of Others

Building on phase locking in the auditory nerve and skin is the emotional mode of relating called acceptance. In a group rapidly assembled for survival purposes, each member must quickly emotionally relate to the other members in the same way. In particular, they must each view one another’s existence as legitimately as they see their own. The members of the group are not acting in uncritical acceptance. Rather, the emotional manner of acceptance does not require any other member of the group to defend and rationalize their existence. As a result, in the group, it is held that each member’s existence is as valid as everyone else’s, leading to coexistence, cooperation, altruism, and protective actions of others, and a stable, cohesive group with the resilience needed to overcome disaster, but not persist as a group. Acceptance forms the relational foundation for survival by establishing the substrate of social process (Maturana & Verden-Zöller, 2008).

Consensuality

According to Baeza-Flores (2022), “‘consensual’ implies that there is consensus, and there is consensus when there is unanimous consent” (p.82). To contribute to the meaning of consensuality, Mingers (1995) writes that language is a “consensual domain, implying that the tokens we use in our language do not have meaning of themselves but depend on a consensus among the people involved in the language” (Mingers, 1995, p. 36). Between Baeza-Flores (2022) and Mingers (1995), language arises as a domain where the symbols of verbal or non-verbal language are not meaningful in and of themselves; rather, meaning is dependent on the agreement of the members of the domain arriving at a unanimous consent as to what the symbols in the domain mean. Of course, a consensual domain could be widened to include other tokens, such as tools and environmental cues, including threats, hazards, rates of change, and trigger points for different patterns of action. There does not need to be a logical connection between what is in the consensual domain and the behaviors and interactions they orient people toward. The tokens within the consensual domain are significant only in the action and language they trigger (Maturana, 1978). The ongoing act of adding tokens to the consensual domain is a social activity, as it requires unanimous agreement, or it is just something added to the domain. As a social activity, it adds the last layer of social process to this theory as the members of the consensual domain continuously decide what “things” mean together.

A consensual domain is one of shared meaning. Baeza-Flores’s (2022) “unanimous consent” is dissimilar to standardization, where one symbol means one behavior or set of behaviors. The energy to establish one universal meaning (and what it triggers) per token would consume energy and time that the group assembled for survival does not have to spare. Instead, it is discovered that tokens often have different meanings. Although they have different meanings as tokens to different members of the consensual domain, these different meanings are unanimously agreed upon when this situation arises. Shared meaning can still exist when tokens have unalike meanings, provided that dissimilar meanings are shared and are commonly held throughout the group and lead to the same behaviors. It is far faster to accommodate someone’s culture and its meaning than it is to change it.

A theory of transitory survival groups is assembled through phase locking, the legitimacy of the other, and consensuality. All three social processes can be animated to take place expediently to form cohesive and effective transitory groups quickly. With such a theory put forth, it must now be situated in the survival context in which it aims to explain.

To Survive

In the context of natural hazard disruptions, dystopian speculative fiction does not have much heavy lifting to do. All one needs to do is imagine what has already happened, for exmaple, heat events and seasonal changes, the 2024 Hurricane Season, and the early 2025 Fire Season in Los Angeles while considering the trajectory that is already present and the assumption that it will not reverse direction. A dystopian and speculative fiction approach makes the imagining material through the written word and takes the future situation further in terms of severity to illustrate a scenario that could occur. It is important to note a few key assumptions. The first is regular resource scarcity, not only in public safety resources but also in food. Second, there is a vastly different hazardscape than is present in 2025, and a much different social landscape that has been thoroughly divided. To situate this theory, consider the following scenario:

Pressure I

It is 2100, and after years of successful suppression, wildfires occurring from Los Angeles to San Bernardino have been burning for weeks. The situation was continuously worsened by new starts caused by arson. It was a highly complex situation with nowhere near enough resources, extreme fire behavior, no means to gain anywhere near total situational awareness, no legitimate strategy or tactics, overwhelming home loss, mass evacuations, and frequent extreme winds. One day, seasonal winds with gusts up to one hundred miles per hour sent a fire fueled by wind and drought-stricken vegetation up to a large community settled mid-slope at the edge of towering brush-covered mountains.

In 2100, across public safety, there are no fixed ideas of what a hazard event will do or is capable of. It is assumed that each event will transcend what anyone involved was even capable of thinking of or imagining. There was a strange comfort in that. The new fire's rate of spread was estimated at forty thousand acres an hour as it defied modeling. There was now, once again, another large community threatened by a wildfire that no one could accurately and confidently map its perimeter. It was spreading and sending spot fires ahead of itself too quickly to have any accurate account of where the fire was burning, where it was not, and at what velocity.

It was not until the late hours of the night that an evacuation order woke up the community. One cul-de-sac of ten homes backed out of their garages in unison, got out of their cars, peered over the guard rail, and considered if they would be fine. They took this opportunity to introduce each other after having lived together for over five years, as communities were largely reclusive in 2100 due to the heat and various social divisions. Another homeowner pointed to the flaming front and, yelling over the wind, named all the communities that had already been lost based on the path of the fire, entering them into the group’s consensual domain. The same homeowner saw the legitimacy of everyone else's existence and stated they needed to evacuate right now, as none of what they had was worth running a high risk of dying for. Their words disengaged many others from their previous thoughts of surviving the fire by staying.

The group contemplated for a few seconds. Though they had just met, they could not help but locate each other's voices spatially and their timing while feeling the vibration of the wind on their arms, superficially and deeply. They were synchronized to a key element in their environment and the speaking, or shouting, of the people in it. Another voice was heard saying they agreed and that it was absolutely time to leave, and the rest of the group concurred.

In their first act of survival, as they quickly became a group, the caravan of adults and children left the cul-de-sac that they assumed would be gone by morning. As the evacuation notice had no specific details, they turned left and headed downhill for ten minutes before encountering a few embers that collided with their windshield like snowflakes. They thought nothing of it until the eight-foot-tall brush on the side of the road started igniting as if it were made with gasoline and started burning in their direction. After awkward ten-point turns between guardrails, the caravan, through a text chain of the recently shared numbers, took a risk and headed towards the only option left: Summerville.

Summerville was about an hour away along a mountain road that posed an extreme risk in the current situation. There was a fast-moving fire that they did not know where it was, and they would be traveling along a road built into the side of the mountains. The text chain unanimously agreed that "run" meant to abandon the vehicles and head to safety. Seeing as there was no other way out, they would have to make one of their own. They also consensually agreed that "fire" meant there was a fire along their route, while "fire threat" meant there was a fire that was going to impact the vehicles. A second person a few vehicles back volunteered to monitor social media regarding the fire. It was mainly the front vehicle's job to communicate these tokens from within the consensual domain. Less than an hour of knowing each other, the group had started forming a consensual domain. No one else could walk into this group and its consensual domain, even at this low level of sophistication, and entirely understand its meaning and the actions the language within it triggers, yet everyone in the group did.

Pressure II

With no information on the evacuation notice, it became apparent that many others had the same notion of escaping to the tourist mountaintop town of Summerville. It had an enormous lake separating the mountains from the tourist areas, including hotels, which were generally filled for the summertime and wintertime for the ski areas. The group encountered traffic on the way into town, heading into the hotel quarters. Much to the chagrin of the occupants of the caravan, the mountainside glowed orange from a fire started a few days ago, which the group knew nothing of.

Each car surmised correctly that many mountain communities had been lost. The person in the group who had offered to monitor social media circulated a screenshot of an official release of "massive home loss," and offered hotels for evacuees. At the same moment, the growing line of cars fleeing the fire from down below the mountain appeared to be proceeding unnoticed. It was as if no one knew the evacuees were there and continuing to arrive by the second. After a while, emergency resources directed vehicles to this hotel or that hotel.

The group stuck together and arrived at the same hotel to stand in line for an hour before they finally were face to face with the hotel manager. The text chain read: "We have to get out of here." The group asked the manager about food in town, and they replied that the one grocery store in town had not received a shipment in two days due to the fire, and inventory was certainly thin, but many of the restaurants were still serving. Due to the local and more distant evacuations, it was two families in a room, which the group was fine with. In closing, it was asked if there was any other way out of town. The manager replied that the way they came up was now an active fire scene along the highway, and was threatening to come this way. There was one more road out of town, but it was closed as the fire from two days earlier had burned on both sides of it, leaving hazardous trees.

The group gathered in one room and made plans to try and find breakfast and check the grocery store. They decided to leave half the group at the hotel and take orders over the text chain. Five left the hotel room and headed down the hill to where the restaurants were. They went to the first one that was open and stood in a very long line in the smoke and heat. Two left to check the grocery store. While the remainder were getting to know each other and mourning the loss of their homes that were within the burned area on the updated map, a large group of armed people forming what the group members called a militia, came by yelling that this food was for locals only and should not be given to those from out of town. They yelled that the town had lost a lot, too. There was plenty of face-to-face intimidation and failure to ask to check identification to ensure only the locals would be fed. The three stood their ground, now standing on the steps of the restaurant, ordering food while the militia yelled that out-of-towners should not be served.

The five made it back with everyone's food and communicated that they had heard the restaurants were running low. It was also explained that there was not much left at the grocery store, mostly items that would require a full kitchen and random cookware. Most importantly, it had only been hours, and there was already a division forming between local and non-local. One of the five who had been down in town communicated that it could very easily become dangerous. In the course of their speaking, "militia" entered into the broader consensual domain, which triggered actions of avoidance and a distinction containing violence and rage.

A trip to the restaurants for lunch turned into a patchwork of moving from one to the next, still harassed by the growing militia. Signs that there was no food left adorned many windows. The four cobbled together a meager lunch for the group, knowing it would likely be their last until more food was delivered. Back at the cars, all five phones chimed, and in the text chain was an official release from the emergency resources indicating the National Guard would bring food at some point tomorrow, depending on flight conditions.

The five from the group went out to the restaurants one last time at dinner and drove up and down the streets. When they started seeing people walk away empty-handed, they held out hope for a while longer until the crowd passing by their vehicles was chanting that there was no more food. They attempted to leave and return to the hotel quickly, but found themselves in traffic as the sun started to set.

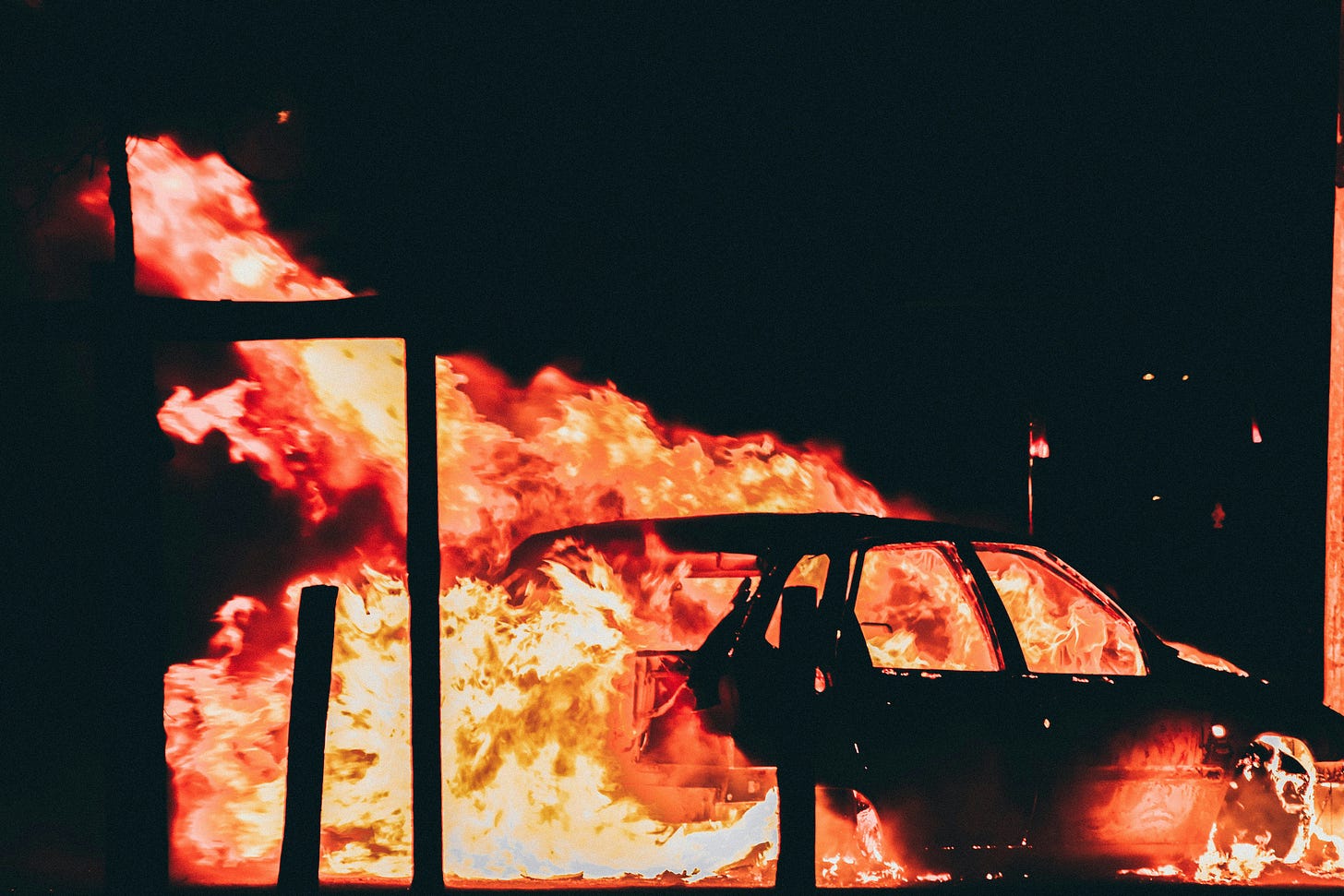

Outrage swelled in the streets. One of the five said “militia” anticipatorily right before the militia turned the corner and walked down the main street. Some evacuees from down the mountain engaged them and other locals. After a rapid escalation, physical violence erupted so vastly that it filled the street. It was soon after that the breaking of store windows, outdoor stores, liquor stores, candy shops - anywhere where there was something to eat. The local police soon got involved, but the scene was too large. Arrests were made where they could be, but the now-mob went from street to street fighting, robbing, and destroying property throughout the night. To everyone’s amazement, it took, for some, only a day’s worth of not eating, or just barely, for physical violence and destruction to emerge at scale. At this point in the future, an impressive amount of society was just waiting for an excuse to erupt.

Back at the hotel, through words, descriptions, and explanations, the group communicated in a way that belonged to them through unanimous agreement. The five told the others that there was no food left, and they had narrowly escaped being swept up in a wave of violence and destruction. They had watched the entire tone of the town shift as food vanished. Pressure had been building since before the group had arrived, with the loss of so many homes and their scenic mountains earlier in the week. Tonight was not the end of it, everyone agreed.

In the morning, a police barricade blocking downtown could be seen in the distance, and wisps of smoke rose into the air. An upside-down vehicle could be seen on the other side of the blockade. Unfortunately, the food arrived about eight hours past its estimated time at the high school football field, where the earlier release said it would be. Rows of people were pressed up against the fence that bordered the running track that lined the football field, shouting at the local and additional law enforcement that had arrived by helicopter earlier in the day. Many others were sitting on the grass, waiting for their turn to receive food. The orderly line that had been established earlier in the day had devolved hours ago. The group continued to relate to each other as legitimate and, in doing so, saw that they should continue to divide the group and, once again, leave the children with caregivers back at the hotel, and the same five would gather food and any water that may be available. They did not simply and unquestioningly accept the existence of the children, but accepted that they were children with an existence that was equally legitimate as their own, but in need of additional consideration and protection to be treated as equals.

Pressure III

They were heard before they were seen. Multiple helicopters soon came into view with large nets underneath them. Everyone was suddenly on their feet, ignoring the gate protected by local police in riot gear. The implicit social order had already decided this would be a free-for-all, and the majority were simply waiting for the food to be on the ground. One by one, the nets touched down, and emergency resources unpacked them. Following protocol, they then began to count each case of Meals Ready to Eat (MREs) and twenty-four packs of water. The delay infuriated and confused the onlookers, and any type of reason was drowned out by yelling. In the minutes that followed, the pressure overcame the rows of people stretched all the way around the perimeter of the running track, and those who had been sitting down moments earlier were on their feet.

Anyone who might have been identified as militia was the first over the fence in all directions, running at a sprint towards the food. Some were stopped, but the totality of the circumstances did not merit action by law enforcement, who started running towards the food to support the emergency resources, who had already left the scene.

Nets were ripped open rapidly and ravenously, and boxes of MREs and cases of water disappeared under the arms of militia members, townspeople, and out-of-town evacuees. The five from the group were running toward where the nets had been let down, and each had their assignments: three would grab food, and two would grab water. They then followed the mob back over the easily scalable fence, back around the bleachers, and towards the parking lot, which is where they stopped suddenly.

They could feel and hear the yelling of the mob. A traffic jam leaving the parking lot had left too many with food vulnerable. Militia and militia types were rocking cars back and forth and smashing windows, setting them aflame, leading to widespread violence and clashes with law enforcement and some arrests. Food continued to be stolen. Even the threat of continued hunger had turned the town and its visitors into something they were not.

The five who had taken one vehicle that was parked in the lot referred to it as a loss and ran back to where they had come from. They slid down an embankment and ended up on an empty suburban street and hid out of view while calling to be picked up and suggesting to take whatever route would keep them away from the school. One of the individuals shared their location.

A phone call to the five was received, and they communicated that violence had entered the hotel district, and they had to prove to militia members they had no food before they were able to leave. There would be a delay. The five moved deeper into the thicket they were in listening to the yelling and shattering of glass.

The others eventually retrieved the five, and they distributed the food and water throughout the caravan, which was now missing one car. It was decided over text chain that their best chance of survival was to head down the only other road from the mountaintop that had been burned over a few days before the group arrived. They would be traversing the road now without daylight, but all agreed this would be safer than staying in a town overrun by a riot. They came to the junction and turned right, heading down a hazard-filled road.

It was decided in the group chat that once they were ten miles in, they would stop and eat. The first ten miles went by quickly and without incident, and there was time to heat meals and open a case of water away from trees before carrying on. Still, they could not help but feel they were being chased or watched from above the road. While they were eating, every tree that fell inside the burn, every tumbling rock, led them to believe that they were not alone briefly. Yet no one came.

The GPS said they were a half hour from a populated area, and that was not showing any fire activity. The drivers were anxiously awaiting an impediment. Soon enough, they found one. Five trees spanned the roadside hill cut and the guardrail. They were not large trees, but moving them would still require considerable strength. Most of the group who were not with the children or watching behind them responded swiftly. They noted they did not need to clear the entire road but just one lane. They climbed up the bank and felt their feet, for the first time, move through ash. Through a concerted effort, and one hour later, the trees were carried and slid halfway across the road, and the caravan rolled on. The vibrations of the trees sliding along the pavement and guard rail had been felt at everyone’s fingertips. Being blocked by downed trees occurred periodically, frequently one tree, seldom more.

The group would have been afraid to learn how many trees had already fallen behind them. With five miles to go, they were stopped in their tracks as the broken trunk of an enormous tree lay across the road, with half of it protruding beyond the guardrail. Exhausted, the group emerged to move the obstruction, which took many original ideas, the sensing of vibrations, dangerous maneuvers, three close calls, enormous strain, one injury, sweat, and the continued cooperation and coordination that had led to their success all night as they all saw each other as equally legitimate and would never imperil another member of the group or let them do so themselves.

The group proceeded with only a few small trees to clear out of the way, and then they found themselves coming to a main road. The GPS instructed them to turn left, and once the way was clear, they headed toward food and lodging. It was now three in the morning, and one person from each house went to secure a hotel room. Meals were being heated up for the group by those back at the car on the pavement. Covered in ash, they enjoyed one of the finer meals of their lives and stayed in the parking lot until four in the morning, talking about the militia, the food shortage, the riots, attacking people in their cars, and the loss of their own homes and what the next steps would be. They suddenly found themselves with no place to go.

The group said they would stay in touch, but the purpose of the group had come to a close. They had survived the fire, a riot, food scarcity, a food shortage, a violent mob, and traveling a dangerous burned-over road together. Perhaps survival is a precondition for lasting friendship in 2025, but in a divided society, it has lost its value as a relationship adherent. They went into their hotel rooms and left at different times in the morning, and the text chain was silent. They had all survived, and that was the purpose, and through phase locking, consensuality, and the legitimacy of others, they had quickly come together in the name of survival. Deeper connections could have been formed over a great time period, but they were not required for survival.

Conclusion

The group was formed for the purpose of each member surviving, and it dissolved after this purpose was met. While it remained a group, its social process, behavior, and capacities can be explained by the theory assembled earlier. Phase locking begins the post-analysis of the group's social behavior and is perhaps the most prevalent, as it is autonomic; one cannot help but do it with the spoken language of others and the environment. Even in the wind gusts up to 100 mph, as the group was starting to come together, voices could be detected and localized with roaring background noise due to phase locking (Peterson & Heil, 2020). Vibrations from the group's verbal language resulted in phase locking throughout and additionally through the Meissner corpuscles when moving logs across the pavement and over the guard rail. Phase locking offers a rapid way to achieve synchrony but does not replicate the congruence achieved through temporal structural coupling. As a result, the same depth, richness, fit, and synchrony of relations among people is not present with phase locking as it is with structural coupling. However, phase locking in the context of transitory groups is sufficient and functional for communications and environmental sensing.

The group consistently demonstrated an omnidirectional relationality to the other members, where they saw their existence as legitimately as they saw their own. Doing so made the other members more than just a loose association. By seeing each other as equally legitimate, social process began above the autonomic level of phase locking.

The case of the children requires some additional consideration. Their existence was unquestioningly accepted as being as valid as everyone else's. However, to maintain this validity was the added provision was that to maintain this existence and treat it as legitimately as their own, additional measures would have to be taken. For example, not bringing the children down to a tension-torn town to get food from restaurants was, in a manner of relationality, treating their existence equally to everyone else's. Their existence was seen as equal, and for that reason, the children were excluded. This shared view of everyone's existence is as valid as everyone else's contributed to cohesiveness. The members acted in the interest of the group in their decisions and actions, and no one left the group in pursuit of their own individual or family success. The shared validity of existence is exemplified by the five who eventually found themselves in hostile territory but kept going back into town anyway. They still saw their existence as legitimate as those back at the hotel, but to actualize that, they needed food, as did the five standing in the street, whose existence was still valid; they were assuming risk for the existence of themselves and others.

Consensuality was a cornerstone of the group's behavior, social process, and operations, and is only loosely tied to the duration the group has existed. The group came into form between the failed first evacuation and the trepidation-filled climb to Summerville. During this time, they referred to canyons and communities by their locally known names and introduced tokens (words) that would trigger emergency-reactive behavior. The word "militia" became part of the consensual domain and served as a significant distinction for those who wanted the town to belong to the locals, who were mostly armed and posed a danger. The group was continuously forming a consensual domain as if they were rolling out a carpet ahead of them to walk on. It was the consensual domain that allowed the five to describe the riot from the first night accurately, and then the one the next day at the food drop. While they had not been together long, they had been communicating enough that words, explanations, and descriptions came to have shared meaning quickly and improved the cohesiveness, coordination, and operational capacity of the group.

Given this fictitious dystopian speculative setting, it appears that the theory of transitory survival groups may have some value in understanding their formation, functionality, and effectiveness. The three elements presented can all act or be applied quickly and support the expedient forming of a cohesive group. Of course, this remains highly theoretical and speculative, but it may have some utility in events already taking place.

References

American Psychological Association. (2025). Phase Locking. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/phase-locking

Baeza-Flores, M. (2022). Humberto Maturana: Biology of the knowing for beginners.

Bajwa, H., & Yasir , K. A. (2025). Physiology, vibratory Sense. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31194428/

Bear, M. F., Connors, B. W., & Paradiso, M. A. (2007). The auditory and vestibular systems (Third ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Healey, V. (2025). The hearing mechanism. Oslo, NO: Publifye AS.

Keen, D. (2008). Complex emergencies. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Maturana, H. R. (1978). Biology of language: The epistemology of reality. In G. Miller, & E. Lenneberg (Eds.), Psychology and biology of language and thought: Essays in honor of Eric Lenneberg, (pp. 27-64).

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1992). The tree of knowledge. Boston, MA: New Science Library.

Maturana, H. R., & Verden-Zöller, G. (2008). The origin of humanness in the biology of love. (B. Pille, Ed.) Exeter, Devon, UK: Imprint Academic.

Mingers, J. (1995). Self-producing systems: Implications and applications of autopoiesis. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing.

Peterson, A. J., & Heil, P. (2020). Phase locking of auditory nerve fibers: The role of lowpass filtering by hair cells. Journal of Neuroscience, 40(24), 4700–4714. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2269-19.2020

Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Turecek, J., & Ginty, D. D. (2024). Coding of self and environment by Pacinian neurons in freely moving animals. Neuron, 112(119), 3267-3277. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2024.07.008

Phase locking as it pertains to social process. Brilliant!