A Question About Design: Is Music Composition Dead or Alive? Limited Edition #00000000000

In the Spirit of The Cassette Series, an Examination of the Obscure Notion of "Dead Music" Released in 1995 in Italy. Presented Here in Connection with Alive Music, Autopoiesis & Design Style.

Preface

More content is coming for those who follow this blog exclusively for wildfire! But do not leave just yet! Please enjoy a post that has been waiting to be published. Imagine it as a reel in a recording studio that has never been heard until now.

We all design constantly. This post is about how music can define and support distinct design styles that may be used in wildfire innovation. As a design expert, I welcome all readers to enjoy this unconventional post, which offers valuable insights into understanding music, design, and their intersections.

In addition to fire, GregoryVig also explores design, complexity, biology, and resilience, which are all part of the larger project of this blog and apply to wildfire and any other risk management work. The following post explores design by analyzing two forms of music composition that can be translated into two distinct product design styles.

All fields should recognize design as innate to human behavior. Design is roughly comprised of the two connected acts of deciding what should exist based on data, preference, vision, need, or desire and intentionally bringing it into being. My work in design around wildfire and emergency management dates back to 2016. This post represents my current thinking on design. True to the Cassette Series, music is integral to this post, forming its very foundations.

If you are new to the Cassette Series, it is an aesthetic and the celebration of a perceived intersection between music, writing well, and early cassette culture's subversion of formal music institutions. While the author does publish, it is firmly held that not all writing should be behind paywalls. Early cassette culture saw the appearance of now-famous artist-owned labels that would publish avant-garde music at a rapid pace. Embracing this culture to the degree feasible had always been the goal. A “Do it Yourself” attitude prevailed. For releasing writing (cassettes), blogs are equivalent to the artist-owned label.

From its first tape, the Cassette Series has made it clear that the author recognizes a unique link between listening to music and writing. The series has also been open about its influence, namely older industrial works released early on, such as tapes ranging from noise to power electronics to death industrial and a few extreme metal bands. This post emphasizes the cassette and music and the role it can play not only in writing but also in other design contexts.

Introduction

In 1993, an unwell industrial artist whose death-obsessed tapes cut across death industrial, power electronics, and noise subgenres started to record and release works under the artist’s independent label and their moniker. Two years into a frenzy of abrasive, foreboding, violent, and yet engaging and emotionally evocative releases, on October 14, 1995, the artist put something out into the world that is nearly impossible to make sense of, and very little has been written about. The release was packaged in a VHS case and advertised on the cover as a Limited edition of "000000000000000000" copies.” The famed Slaughter Productions released it based in Sassuolo, Italy. The VHS cover also indicates:

“‘000000000000000000’ is an example of real ‘dead music.’

Note: Do not use a tape recorder for listening just use your brain and think that music is DEAD.”

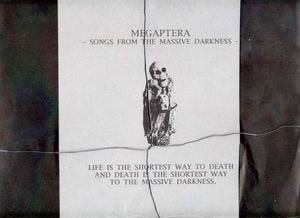

There is plenty to unpack there, but first, an image of the contents of the VHS case:

The blog “Anomaly Index: Music's conceptual anomalies and wanton obscurities” (2020) reports, “It was a box for an old VHS tape which, when opened, revealed the mangled parts of an audio cassette laid on a bedding of burnt cotton” (np.). In the blog, this work is called an “anti-cassette” without an obvious motivation. The author or authors of the blog include, “but the packaging includes a clue, the cover describing it as ‘an example of real ‘dead music,'” which suggests this was yet another manifestation of his long-standing fascination with death” (n.p.). The central theme of death and surrounding topics of pain, isolation, and suffering found in this artist’s tapes are consistent with the writings on the blog last year. The artist's occasional deviations from these emotions and related topics are far from endorsed by this blog.

Alive Music

This strange release questions whether death is pervasive among living and non-living things. It is necessary to consider whether music can be alive and become dead or vice versa.

“The strictly physical systems persist without living: they disintegrate without dying; they are half-alive or merely half-dead. Only the most complex form of living organizations corresponds to being that undergo the completion of death” (Morin, 1993, p.235).

Morin (1993) doubts the inability of dead music to exist, at least as it relates to the cassette, which will “disintegrate without dying.” The artist has aided this process by destroying the tape, which was never alive but always half-dead.

Is music alive? Maturana's autopoietic criteria will be used as a litmus test to evaluate whether or not music can be considered alive. As an author who uses biology as intended, any determination will be made through metaphor, imagination, and contortion of the original meaning. Still, this will be useful for the ongoing discussion moving toward design.

Maturana and Poerkson (2011) explain that living systems are constituted by a “network producing molecules that interact with each other in such a way as to produce molecules, that in turn, produce the network producing molecules, and determine its boundary” (pp. 97-98). This type of network is autopoietic, and the primary example is the cell (Maturana & Poerkson, 2011).

A fabricated scenario will be used to demonstrate this point.

Even a small sampling of the artist’s work reveals a wide range of possibilities a tortured mind can create with even a simple setup where a synthesizer is dominant. A synthesizer, effects, a mixer, and a microphone made incredibly meaningful, haunting, sinister, and complex music. It is visible that the different sources of sound form and exist in a network pattern where past, current, and anticipated activity at one node, or source of sound, affect changes in the other nodes in a continuous reciprocal exchange. In this network, each key on the synthesizer is considered a node, as are the effects built into the synthesizer, any external effects applied to the node, mixing, sparingly used vocals, and any effects added to them.

The network's remarkably uncomplicated arrangement quickly increases the number of nodes and connections during composition. At any moment, the network of instrumental activity produces sounds that interact with one another to make the shortest portion of a musical track. The networks created by the artist each produce a single or collection of sounds constituting an instance of the entire piece of music and establishing its boundaries. It is the way the products of these networks relate to one another in such a way that, from these interactions, music emerges. An entire piece of music is an emergent property. It is not found in any of the networks or by adding them up, but how they interact from the song’s beginning to the end. How a section of music heard in the here and now is perceived is influenced by what has already been heard and what the listener anticipates will be heard next. Music emerges from instant to instant on a small and medium scale and a large scale from beginning to end. The emergence of a piece of music includes the overall impression and emotion it leaves behind as the next one begins.

In live music, there is a variance from Maturana’s criteria in that the network producing sounds that create a part of a song does not then reproduce the same network that created it. The composer creates a network of instruments and vocals, but the prior network pattern is rarely reproduced; the network is not sustained. Instead, new networks are created. In a departure from Maturana’s conception of life, barring the artist’s use of repetition, new networks are perpetually being created as the song progresses. The exact node activity and the interaction pattern among them depend on the sound the artist deems appropriate based on the sounds already made, the anticipation of what should come next, after that, and so on. The preceding sounds created by artist-designed networks influence but do not determine those more or less likely to occur as the song progresses. The artist creates networks to produce sounds that will carry their expression forward.

Using Maturana’s autopoietic criteria, this analysis shows that the music-making process can be alive, even though the same network is not continuously produced. Instead, barring repetition or choruses, new networks continuously sustain the music as alive.

After the music is composed, its aliveness dissipates. The listener responds to the emergences throughout each track. What is heard is something made through a process that was (metaphorically and imaginatively) alive through the continual creation of networks, one after the other, that are in some way related but generally not the same. The networks continue to carry some melody or artist’s intent as a thread that runs through the networks, even during transitions. As a listener experiences it, music is not alive as it was during composition. What the listener hears is half-alive and reconstructed through their listening to the artist’s work. The artist’s process of continually bringing life into each track has ceased. This process has been completed and no longer requires an artist or someone else to bring life to each track through composition by intelligently creating the right sounds at the right time to convey the correct expression. After the album is completed, it is released in physical or digital formats with notable traces of the artist’s pursuit to create something full of life during recording.

Recorded music is not alive. It was during composition. The physical cassette is undoubtedly half-dead or half-alive. Either one can be debated. However, the music heard involves the same networks brought together in composition and the properties they create in a flow of varying network configurations. Together, even a simple array of synthesizers, effects, and vocals, through talent, anticipation, and involvement in the world of the track, creates coherence, melody, and pattern. As it is heard, alive music is experienced more half alive than half dead. This depends on the motivation during the composition process and the style adopted - alive or dead.

Dead Music

A slight stretch of Maturana’s autopoietic criteria suggests that creating music produces something alive. A fine line is walked in making this declaration, but it is sufficient for the conversation. Dead music does not arrive through the artist’s destruction of a cassette that is “half-alive or merely half-dead” (Morin, 1993, p.235) and can be destroyed with dying. The artist asks us to think that the music is dead and not to use a tape recorder to play it, which would be impossible.

If dead music is not created through the destruction of the tape, how is it made? Dead music is a broad dismissal of live music principles and a style of composition as the same arrangement of mixers, microphones, and synthesizers can be used to create alive music. Perhaps a broken cassette labeled dead music is simply another obscure expression of the artist’s obsession with death materialized through low, haunting, harsh, and sometimes erratic synthesizer tones with occasional vocals, samples, and effects. Dead music renders the likely contents of the tape not only music about death but death in composition. Would-be listeners will never know for sure.

Elsewhere, referring to the previously mentioned side project, the artist continues to describe their musical style as dead music but expands on the idea. They say it is cold, like a corpse, and beyond life, space, and time. Dead music is composed by an artist with nothing left for a brain that creates music that travels into nothing, an empty space that continually repeats itself, a space where there are no exits. The artist continues to live but is dead, similar to Morin (1993). Their obsession with death takes on the form of dead music made by a dead brain. From this perspective, composing dead music may arrive naturally for some.

Dead music can be created intentionally through composition. Like alive music, dead music may include any number of instruments and effects, creating an overwhelming number of possibilities for interaction and generating entangled network shapes capable of producing any number of sounds that could contribute to an instant in the flow of music. What makes dead music dead is the intentional absence of interaction or relating among the nodes that would form a network. At one level, each instrument and effect may operate without concern for what the others are doing, or just barely and not through time. A style of composition where sounds are not concerned with one another avoids interaction. Groups of networks may produce coherent sounds over shorter time frames. Still, dead music uses unexpected and violent transitions that destabilize and deconstruct melody, stability, and the ability to anticipate what will happen next. Dead music does not aim to produce recognizable melodies and themes in the ongoing flow of the track. Instead, it is cold, obtrusive, anxiety-provoking, foreboding, and unexpected. Dead music does not flow; it is forced by the artist and driven by negative emotions into a space of nothingness without exits. With no exits, the steadily increasing nervous and anxious energy cannot escape and cannot be bled from the track. It is a gift to the listener. Listening to dead music, there is a growing tower of cognitively unresolved harsh sounds without specified meaning that continue to reverberate with no coherence in the emptiness evoked by the “music.” From the minds of the maniacal, obsessed, and even those who find themselves alive but know they are already dead, there is dead music.

Looking at a mesoscale, dead music is also produced through an intentional lack of concern for networks relating to networks to a certain degree. For example, some artists compose static with slight dynamics, while others stop short or produce white noise. As mentioned, dead music can contain stretches of networks that produce a melody, such as in the background of a repeating suspenseful arrangement of tones that lasts the track’s duration. In the foreground, networks may exist as already specified without constructing “musical” sounds. Networks of nodes are designed in weak association with those to follow or not at all. There is no causality to make sense or answer why one instance of sound came after the other without repeat listening and analysis. There is also no chorus to create a repeating pattern. Intentional disorder reigns. When speaking of dead music, it is a random and indecipherable sound designed to be something not to be understood, but by a microniche of listeners. Dead music operates almost on an emotionally evocative level. There is death, pain, suffering, and anxiety to be felt. This is quality inspiration for writing in troubled times, communicating a horrible experience, or genuinely feeling and describing the world. As none of the sounds in dead music typically interact, there is no emergence from moment to moment. Regardless of the section studied from a piece of dead music, it has no conceivable connection with those that came before or will follow after, so there is also no overall emergent impression, meaning, or significance that can be derived from each song. Finding meaning is left to the listener.

It is a far gentler task to think about dead music than it is actually to listen to dead music.

The independent use of the various instruments and effects that do not form an intelligible network and arrangement of networks and the rare patterns and sections of a track that have some consistency and repetition produce dead music. Dead music is post-music, such as the disturbing and mysterious “group” Gulag. This group is undoubtedly dead music, as they exclusively create abysmal sound with constant screaming without coherence, melody, or ability to anticipate or discern what is being heard next. Gulag is devoted to dead music through violent, harsh, overwhelming, and disturbing sounds. The point of Gulag is not to release alive music, or anything of the sort. It is dead music, by definition. There is no sense. In a way, the group has not created anything to hear. It is the A.M. radio on maximum volume with painful sounds calling out for death. Both alive music and dead music are made with commitment and conviction. Dead music requires a certain amount of discipline, not following what may be a natural tendency to create rhythm, pattern, and melody and overcoming these instincts. Instead, dead music artists act well beyond what is normative to express something from a place of severe pain, malcontent, malice, social observations, loss, grief, and isolation that resonates with a loyal niche audience.

Within the broader context of the 1995 release, the two-album run of Project Death (translated) by the same artist debuted in 1996. Project Death can be categorized in a few different ways, one of which is dark ambient. There is an unusually heavy use of untranslated Italian vocals. Interviews suggest the English-speaking audience is missing the value of these lyrics. These two albums are categorizable music despite being a project about death. It may be supposed that Project Death would make dead music, but this is false. While the distinction between music and non-music is listener-dependent, much of Project Death has recurring sounds, more considerable repetition, and an ongoing flow with various transitions. Overall, Project Death does not deliver the dead music theorized above. Music can be about death without being dead music. Music can even be alive music and be about death. It is not the subject but the composition.

Why Write About Dead and Alive Music?

In addition to dead music’s connection with one of the themes running through GregoryVig’s 2024 blog posts, the idea of dead and live music has implications for design. Regardless of what is being designed, whether it is a blog post on an obscure anti-release from decades ago, a plan or strategy, a floral arrangement, a chair, a table, a carefully manicured social media post, a poem, a song, a or hammer, dead and alive music can form a design style. In what follows, a dead music design style is identified as uneven design and an alive music design style is termed even design.

Uneven Design

Is the design process alive or dead? Whether the design process is even or uneven is consequential for the finished and released design outcome. Bad even design can be experienced as uneven. The resultant user experience of a designed product that knowingly or unknowingly was brought into the world through an uneven process is discontinuous, mentally taxing, and demands something from the user. It does not simply hand itself over for use, as with even design. In uneven design, the lack of networked nodes within the user experience leaves the individual to figure out how to put the elements they can interact with together, requiring mental exertion. Like in dead music, in uneven design, concern with how all the features make sense across the scale of the interface is minimal. The designers did not provide the user with the cues and constraints needed for a smooth user experience that does not demand energy or attention. Uneven design may produce a no-thing requiring the user to identify how to engage with it. Design modeled after dead music is not entirely without merit. Dead music, or the idea of it, may provide the basis for an uneven design style. Dead music is a fitting inspiration if the idea is to confuse, scare, misdirect, make the relationships among events unclear, and provide an austere and uncomfortable experience desired by a microniche audience, just like dead music. Uneven design may be desired by those who want to figure out the design themselves, the “D. I. Y. or Die” crowd, and those who want to customize it, understand it, or have a specific experience with a product and its use.

A document written in an uneven style may produce content similar to the scattering of ideas like stones tossed across a frozen lake. The stones are strangers to one another. Their connection is that they are present in the same location; it is nothing more than this. Writing a paper (design) is not unlike writing a song; it can be an uneven paper as just described or a paper following even design that presents networks of ideas that fit within the more extensive network of the paper. There is a hermeneutic between the sentence and the paper, and the paper and the sentence that increases user experience through even design that makes everything obvious.

Even Design

The use of dead music to inform a designer’s uneven style, including process and outcomes, also applies to alive music and an even design style. Even design is founded on the principle of not asking for attention; the designed artifact does not beg for the user’s attention to be able to understand and interact with it. Even design is easy and pleasant, avoids breakdowns in user experience, and is intuitive.

A written document in the composition phase, whether a blog post, a white paper, an industry publication, or an article for peer review, may be brought into being through even design. For high-level analysis, the author may share the key, abstracted insights, and emergent properties from the networks, not the networks themselves, to provide a better user interface that delivers only the desired value. In the greater body of text, with transitions varying from sudden to smooth, the even design writer presents ideas in a way that makes sense with where they are in the paper and within the larger context of the paper itself with coherence, consistency, and flow. The pursuit of continually keeping the narrative alive through relating one network to the next. A project completed through an even design process produces an outcome experienced by the recipient dominantly in the domain of half-alive rather than half-dead. Even design is intended to be experienced exclusively as half-alive. However, experience breakdowns and the user feeling empty-handed, even briefly, can be considered half-dead.

A designer striving for evenness decides what to disclose to the user. The question is, "How much of what makes this thing a designed thing needs or should be available?” It is a problem of conceal versus disclosure, and even design considers this early. What is “backend,” and what is “frontend?” What needs to be available to work evenly, and what else might be disclosed to go beyond pure functionality and allow customization? Given the market and its diverse array of users, how can the various design requirements be integrated while still creating an even interface?

Conclusion

To the majority of people, dead music like Gulag and artists across many Industrial derivative genres, some of which have been known to release a wall of static with various effects and digital instrumentation, is abhorrent to almost anyone. Dead music is beyond the typical boundaries of comprehending what music is and is not. This distinction of being “not music” does not hurt dead music artists; instead, they embrace it as reaching a goal. Dead music is not for everyone (almost no one), and this is perceived as a measure of success. Relating positively to being labeled “not music” only adds to the strangeness and value of the music. Despite the grating uniqueness of dead music, it can serve as the source for the style of designed artifacts beyond music.

Again, designing unevenly to evoke feelings of strangeness, frightfulness, intrigue, and puzzlement causes the recipient to exert themselves cognitively to determine what is happening or how to use something. Depending on the recipient and their domain, a dead music-driven design style may be entirely appropriate by offering the recipient what they want. The niche or specialist market ideas pursued by uneven design can be a starting point. Through the user’s effort, uneven design may transition to even design in a resolution that moves the user into a smoother and gentler domain that makes clear and immediate sense.

This blog post draws from an enigmatic anti-release of a destroyed cassette in off-putting packaging labeled as dead music that could not be played, only thought of. To understand the possible meaning of dead music, Maturana’s criteria for life grounded in the cell were used first to define alive music. Even design strategies based on and pursuing the characteristics of alive music will appeal to a broader audience. Artifacts produced through an even design style will be easier to use, more consistent, expected, and operate with a better experience, requiring less cognitive load. The aliveness of the artifact being brought into being ends with completing the design process. The resultant outcome is half-alive throughout its use.

The focus of this post is dead music. Dead music is created in composition, not in the destruction of a cassette tape that makes it unplayable. Instead, dead music is created by an artist who generally chooses not to sustain anything within the song, not even in disjointed here and nows. In an uneven design style, emergent properties are recipient or user-dependent and vary greatly. A designer who embraces an uneven style is not seeking to make sense, at least immediately or easily. Still, sense could be made from the designed elements given with difficulty. It is also possible the designer created an artifact that sense cannot be made sense of to encourage a particular array of possible emotional responses. However, this is primarily an approach to music. Uneven-designed artifacts are for niche audiences who enjoy the experience and labor. Either way, there are design choices, and more than one can be made in a process. Will the outcome of a design process be even or uneven?

Sincerely,

Gregory Vigneaux, M.S.

References

Anomaly index: Music's conceptual anomalies and wanton obscurities. (2020, May 2). Atrax Morgue – 000000000000000000 anti-cassette (Slaughter Productions, 1995). Retrieved from https://anomalyindex.com/2020/05/02/atrax-morgue-000000000000000000-anti-cassette-slaughter-productions-1995/

Maturana, H. R., & Poerksen, B. (2011). From being to doing: The origins of the biology of cognition (2nd ed.). (W. K. Koeck, & A. R. Koeck, Trans.) Kaunas, Lithuania: Carl-Auer.

Morin , E. (1993). For a crisology. In E. Morin, & A. Heath-Carpenter (Ed.), The challenge of complexity: Essays by Edgar Morin (T. C. Pauchant, Trans., pp. 231-245). Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. Retrieved 2024